Book Review: Mozart the Performer

In which I write about a musicology book out of friendship 🎼

Overture

The man who would become my closest friend wrote a book about Mozart, and gifted me a copy. This was exactly two years ago. There was no expectation that I would ever read it. It is a book by a Mozart specialist and for Mozart specialists, which is something I am not, though I do like Mozart as an amateur. I read the introduction — the “theme,” in the book’s parlance — and then gave up. Life is short, books are long, and listening to the music directly would probably be a better way to use what little time I have to devote to Mozart in this earthly life.

And then, earlier this fall, I semi-consciously cited an example from the book in my cultural evolution post. It was “semi-conscious” because I didn’t actually read the passage I was paraphrasing, but it almost certainly came from previous discussions with my friend, which were obviously related to his work. It was about musical embellishments behaving as selfish memes that replicate throughout Mozart’s and other composers’ music. After I published the post, my friend gave me the specific pages where he had mentioned those ideas, and upon reading them I found that they encapsulated what I was trying to say quite well. So I edited the post to add a direct quotation in a footnote.

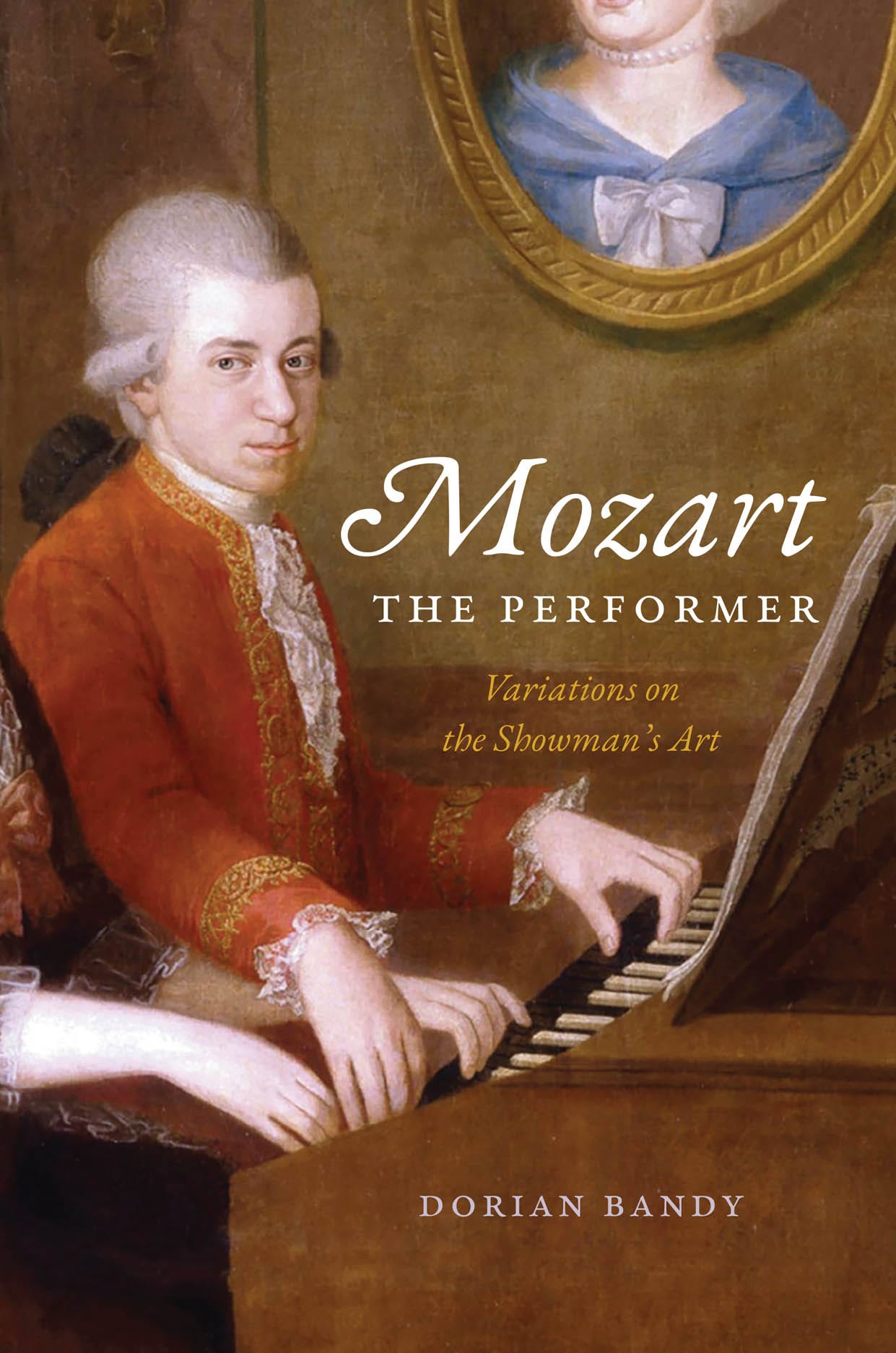

This made my friend so happy! Just this tiny footnote edited late into a random blog post of mine! And therefore I decided that it would be a great gift, and a way to honor the friendship, to read the entire book and then write a book review. So here we are. The book is called Mozart the Performer: Variations on the Showman’s Art, the author and friend is Dorian Bandy. It is available for purchase on Amazon (the book, not the friend).

First Movement: The Cover Crop

From the outside, Mozart the Performer looks like this:

This is not a great cover. My friend agrees. My colleagues who saw me reading the book on an airplane during a work trip agree. Why is that woman’s face cropped out above the lower lip? Why does Mozart seem to have four hands? The cropped woman is Anna Maria Mozart, his late mother, not to be confused with Maria Anna Mozart, his sister. The two extra hands, on the other hand (pun originally unintended), are Maria Anna Mozart’s, not to be confused with Anna Maria Mozart, whose hands are not shown. The uncropped picture looks like this:

Why did the designer make this choice? Presumably the point was to emphasize Wolfgang Amadeus, and moreover Wolfgang Amadeus in the process of performing, given the title of the book. The clear presence of Maria Anna, or Anna Maria, would have diluted the message. Still, my coworkers on the airplane were a bit put off by the apparent four-hand monstrosity.

There probably weren’t many other possibilities. There are fewer than 10 confirmed portraits of Mozart. Several of them depict him in the process of performing, but as the child prodigy that he was (example: the one at the bottom of this post), which is not a great representation of him at the peak of his art. Most of the portraits of him as an adult are static, and some are rather unflattering (example below).

One portrait, of him at the piano, by Joseph Lange, would have been a perfect candidate if only it weren’t incomplete. It is my favorite Mozart portrait, and I used it as the cover image for this post, but the evocation of performance is greatly harmed by the fact that the piano appears only as an unpainted silhouette. Leaving aside the many dubious or inauthentic portraits, we are left with the 1780-81 family portrait and its awkward cropping.

Second Movement: What Is This Book About?

But get past the cover into the book, and everything suddenly feels more artful.

He’s my best friend so you might say I’m biased, but Dorian Bandy writes beautifully. “On paper,” goes the introductory sentence, “a musical score is an intricate but lifeless pattern of dots. But listen to the sounds that pattern encodes, or hear them in your mind’s ear, and you enter an imaginary world teeming with motion.” So do I, as the pattern of letters in the book gets deciphered by my conscious mind. I am reminded that reading, like listening to music, is a rather magical act of information transmission. “But the musical experience goes further,” writes Dorian. “Within this world we sometimes sense the organizing presence of a human mind, a consciousness whose perceived emotional states and overarching worldview bind a musical work into a coherent whole.”

A delightful introduction; and yet I found it difficult to fully grasp what the book is about. The title, and the blurb on the inside flap, suggest it centers on one aspect of Mozart’s life that generally gets less airtime than his legacy as a composer: the fact that he was very much a performer, staging concerts where he would show off as a virtuoso keyboardist. And yes, the book is about that, sure, but I’m pretty certain that Dorian told me it wasn’t a very good synthesis, and having read it, I agree. But then what exactly is the topic?

The best answer comes not in the introduction, but at the end of Chapter 1. The book is about explaining Mozart. Why is his music written the way it is? Why did he embellish this phrase, why does he flout the conventions of that particular genre, why, why, why? Dorian says that many musicologists and musicians avoid thinking in this way, since Mozart’s thoughts are mostly unknowable;1 and when they do look for explanations, they focus primarily on historical and biographical ones. In the book, he discusses those, too — for example, the constraints related to how musical instruments were built in the late 18th century explain some of Mozart’s choices; the identity of the specific people who performed his music explain others — but what he really wants to write about are the aesthetic explanations. Mozart wrote the way he did because he wanted to create expectations and surprise, or suggest dialogue between various instruments, or simulate the hesitancy of an improviser, or craft a theatrical persona for himself.

Explaining the aesthetic choices of a long-dead artist is tricky. They can never be confirmed in a “scientific” way. But you can go a long way with plausible conjectures (for example, my conjectures above on why the book cover designer chose to give the impression that Mozart had four hands). Readers of Karl Popper and David Deutsch will recognize a subtle but real influence of the critical rationalist worldview in Mozart the Performer; I have it on good authority that Dorian is a fan, and both Popper and Deutsch are cited in his footnotes. We can view this book as belonging to the critical rationalist canon, an application of the explanation-focused Popperian/Deutschian epistemology to the niche topic of Mozartian analysis and performance.2

Third Movement: Structure and Content

This exploration of aesthetic explanations is organized into seven parts. The first is called the “theme.” Then follow five chapters, called “variations,” each on a specific way of examining Mozart’s life and work to explain the music: Mozart the Performer, Mozart the Pianist, Mozart the Improviser, Mozart the Decorator, and Mozart the Dramatist. The book ends with a “coda” on performing Mozart.

The designations of the chapters are our first hint that Dorian wasn’t just writing a book: he was crafting one. The “theme and variations” is a common format in classical music, in which a musician plays some melody and then does it again and again by varying everything from the tempo to the harmony to the embellishments, sometimes in a very complex manner. Such a structure is rarely applied explicitly to books, but perhaps it should: it is nice to be able to say that each chapter is a different exploration starting from the same initial idea, rather than some other thing, like a logical progression from one argument to the next.3 The structure isn’t inherently superior, but it’s nice to call it out with a music metaphor. Less well-written books often have more muddy chapter structures.

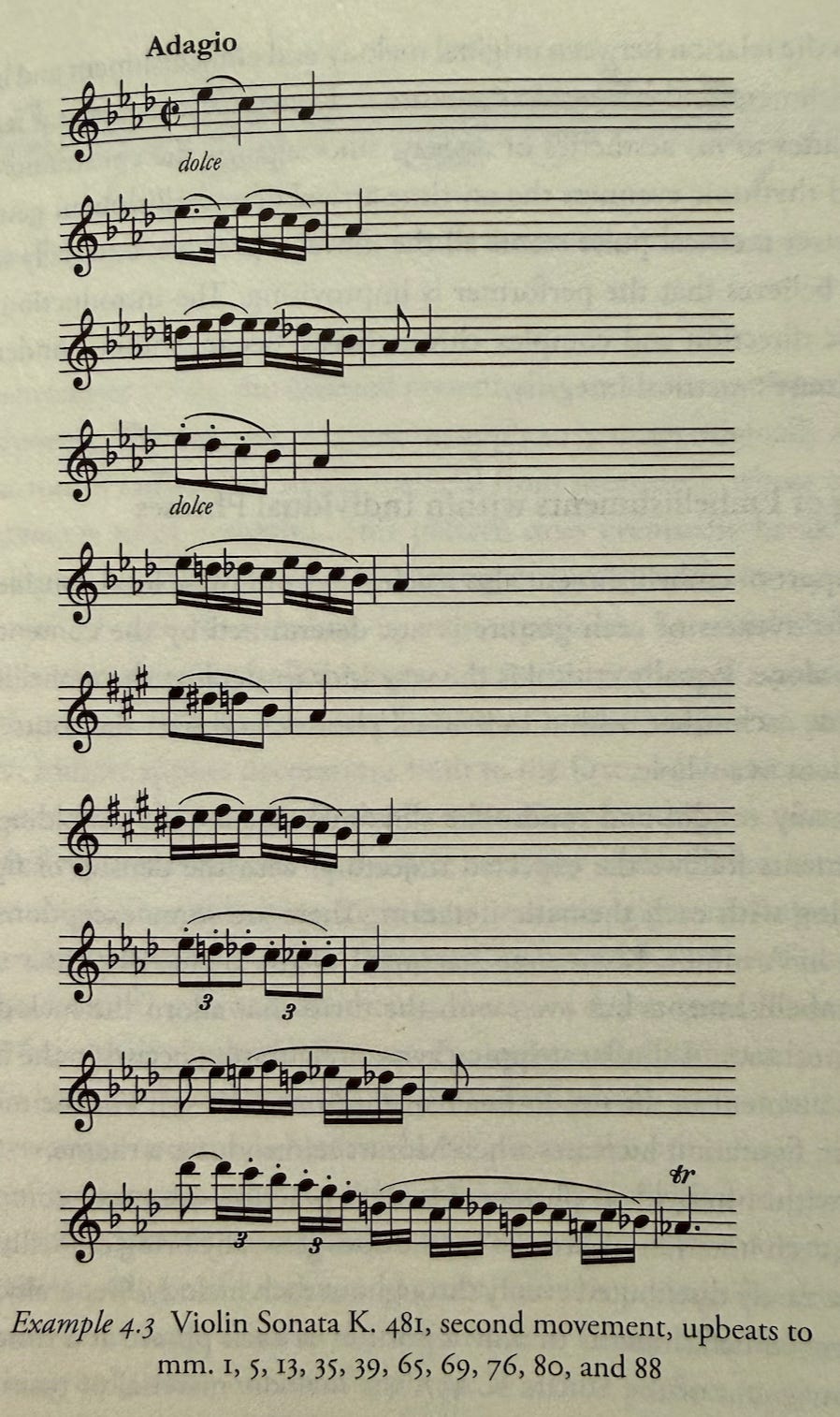

Of the five variations, my favorite was Mozart the Decorator. By “decorator,” Dorian means Mozart’s role of inserting embellishments into his music. An embellishment is to music what an ornament is to architecture: something that isn’t strictly necessary to the main structure of a piece (the melody and harmony), but adds variety, expression, and the possibility of showing just how badass you are at playing the piano. Let me quote the book visually:

Whether you read music or not, you can easily see that the first line consists of three simple descending notes. Each further iteration of the pattern, appearing throughout the violin sonata, explores a different way of performing this descent, culminating in a highly complex line with quick notes that starts at the “wrong” height, for a little too long; varies articulation (staccato vs. legato); and ends on a trill. This creates playfulness and virtuosity. “Mozart,” writes Dorian, “successfully maneuvers the embellishment to its destination but only after playing up the delay and relishing a moment of suspense.”

Most of the book is like that. Dorian discusses some explanations, and gives examples, often with excerpts from the sheet music. The “variations” also get increasingly abstract and complex. In the first one, the explanations center around managing the expectations of listeners. In Variation 2, Mozart the Pianist, they relate to his pianism (new word I learned — the skill of playing or composing for the piano). In Mozart the Improviser, the explanations focus on the fact that musical improvisation was a popular form of performance at the time, and one in which Mozart indulged; and though the improvisations are lost to time, we can see traces of this practice in some of his works, where he feigns incompetence or humorously simulates failures. Mozart the Decorator, as we saw, examines embellishments, including the really cool passage where he sees them as evolutionary replicators; and Variation 5, Mozart the Dramatist, is an exploration of how Mozart stages “musical characters,” including himself, turning everything he wrote from solo piano music to opera into some kind of theatrical show.

When I got to the conclusion, or “coda,” I started underlining the first few sentences, which I found beautifully written. “On paper,” it begins, “a musical score is an intricate but lifeless pattern of dots. But listen to the sounds that pattern encodes, or hear them in your mind’s ear, and you enter an imaginary world teeming with motion.” It took me a while to realize that this was a verbatim repetition of the opening of the introductory theme. (I guess I didn’t pay attention to the coda’s subtitle, “Da capo: An Embellished Reprise.”) After a few sentences, the coda takes a direction that differs from the theme, but reminiscent of it, just like in a piece of classical music. Dorian evidently put a lot of thought into the structure of the book. That’s pretty cool.

Fourth Movement: The Challenges of Reading a Book About a Composer When You Don’t Know Everything Written by that Composer by Heart

The intentionally musical structure of the book is only one of the many ways Mozart the Performer is a good book, but a word of caution is warranted. It was not, for me, an easy read.

The reason is that the book relies on lots of examples, and the examples only work if you can hear the music. A highly skilled musician might be able to sight-read the printed examples and hear the music in his mind’s ear. Another might be so well versed in Mozart that she sees “Violin Sonata K. 481” and immediately knows what Dorian is talking about. I am neither of these. I can sing from memory only a few of the most famous Mozart classics: Eine kleine Nachtmusik, the Rondo alla Turca, the Queen of the Night aria from Die Zauberflöte, the Andante of the Piano Concerto No. 21, the Dies Irae from the Requiem. For everything else, the text did very little for me if I didn’t put in the effort required to breathe life into the patterns of dots.

Fortunately, I do have access to modern technology and a Spotify subscription, so I tried to listen to what I could. There were challenges. I read a good chunk of the book on a flight from California to New Mexico with no wifi. And then many of the examples start on measure 378 or something and I have no idea where to look in the 15 minutes of the Piano Concerto K. 467’s first movement. And then there is Spotify being incredibly bad with numbers, adamantly thinking that when I type “K. 22” I really mean “K. 183”.

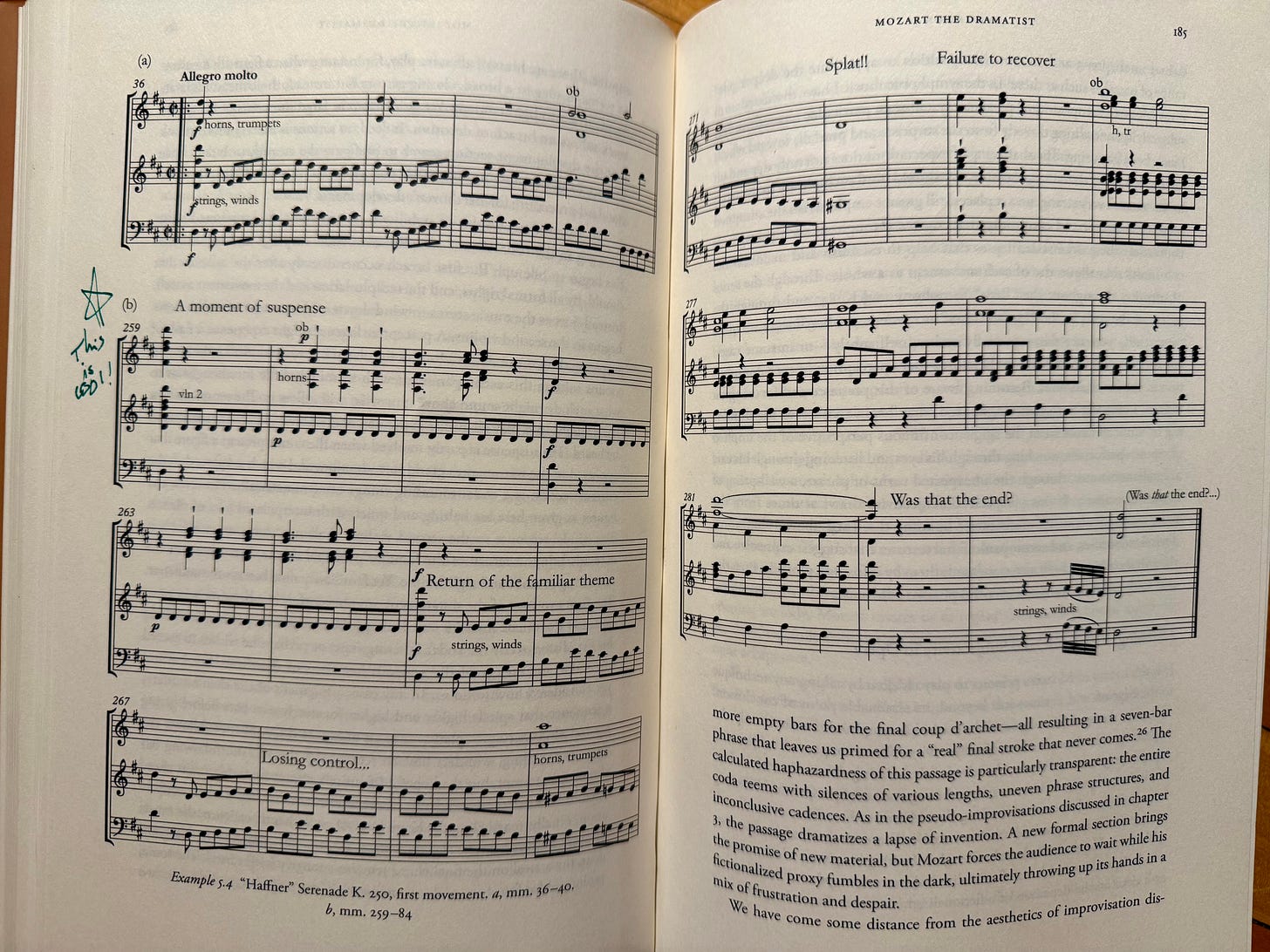

But when I succeeded, it made the experience of reading the book much deeper, and it acquainted me with many tidbits of the Mozartian oeuvre that I didn’t know. My favorite moment — which also contains my favorite quote from the book — was the analysis of the “Haffner” Serenade K. 250, first movement, in Mozart the Dramatist. The nearly two-page sheet music example is annotated with an interpretation of what the music at the end of the movement might be intended to convey: after a very normal 9 minutes of music, we understand that “the ostentatious display of stability is, it turns out, the protracted setup for a gag in the coda.” The last few moments of the piece are an accumulation of surprises: a cadence that isn’t the end, an uncertain moment of suspense, a return of the main theme that immediately seems to lose control, an unexpected ending. And my favorite quote is this single word, used to describe a surprising G♯: “Splat!!”

I didn’t even know the “Haffner” Serenade before, and now, having listened to its first movement a few times, I like it and will be able to recognize it. The book made me enjoy the music more, and the music made me enjoy the book more. Thus I would advise anyone reading Mozart the Performer to either already know all of Mozart by heart, or to take the time to listen to the examples. (I would have asked Dorian for help, if only I hadn’t decided that this whole book review would be a surprise.)

The book did leave me with the impression that it shouldn’t really be a book, but some other type of media. This is tricky, though, because at the same time it really should be a book, and a physical one at that. There is no way I would have gone through it all if it were a webpage, an audiobook, or a video. It was helpful to immerse oneself into the written word; I just wished the correct musical excerpts started playing whenever I needed them to. Maybe we just haven’t invented the right format yet.

Fifth Movement: Humanness, AI, and Love

In the year 2025, one can hardly write anything at all without mentioning AI.

Mozart the Performer was published in 2023, so it could still escape that fate, and does not mention AI at all. It does, however, mention human intelligence. I already quoted this part, from the theme and coda, but let’s quote it again: “Within this [imaginary world created by listening to music], we sometimes sense the organizing presence of a human mind, a consciousness whose perceived emotional states and overarching worldview bind a musical work into a coherent whole.” It is important. Mozart the Performer is about seeing Mozart’s music as something made by the specific human being named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The constraints of performance, pianism, and improvisation, as well as the desire to make music playful and dramatic, “help give his music its elusive yet human quality.”

Imagine we could generate Mozart-like music on demand. In fact we probably already can. I don’t know, I was going to research and try AI music generation for this post, but I immediately got so bored I gave up. I’ve written about AI (visual) art several times in the past, and AI music is probably not very different: useful for some applications, technically impressive, and there isn’t much of a point in fighting it. But it’s also just… less interesting. A big part of why we care about certain pieces of music is the human behind it. That’s why we go to concerts where humans play in real time. That’s why we follow the careers of musicians. That’s why we listen to Mozart playlists instead of generic classical period playlists.

Mozart the Performer is about explanations. And those explanations are all rooted in the fact that Mozart was a human. You could write a book about explanations for AI-made music, but that’d be pretty lame. The model was trained with all the music on the internet, and prompted to “write a symphony in the style of Mozart,” and then you’d actually end up talking about Mozart again, with a side dish of matrix multiplication.

It always boils down to humans somehow. That’s what matters to us. Another way to phrase it is: it always boils down to love.

Dorian loves Mozart, and wrote a whole book about him. I love my friend, and read a whole book by him, and then wrote a blog post for him because his birthday was approaching. In some sense, none of this is very important: the world would continue to function with one fewer book about Mozart, or one fewer blog post. But in another sense, it is the most important thing.

We can uncover some of his thoughts from his abundant written correspondence or other clues such as early drafts to his compositions, so it’s not as bad as many artists for whom we only have the art, but all of that is obviously only a small part of who Mozart was.

The very end of the book also seems clearly inspired by Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity, suggesting that there will be, in the future, better explanations of Mozart’s music, replacing the theories being discussed now, including in Mozart the Performer.

To be sure, everything is connected to everything else in Mozart the Performer, like in any book (or music piece).

QR codes to youtube timestamps would do the trick. Most classical works already have score videos on youtube.

A wonderful review for what sounds like a fascinating book for the right audience. It made want to buy the book so I did, on Kindle (looks great on iPad). I became obsessed with Mozart in the late 80s after seeing and hearing the film Amadeus. I read several Mozart books and bought many more. I collected nearly all of his works on CD and attended many concerts of his music, mostly on business trips in Europe and Japan. I even made two “pilgrimages” to Salzburg. I’m a songwriter who is only semi-literate in reading music, but I have ready access to recordings and I’ve collected PDF’s of many Mozart scores. So I’m looking forward to exploring some new Mozartian niches through your friend’s book. Thank you for your great review.