Cultural Evolution Works in Not-So-Mysterious Yet Often Misunderstood Ways

It's easy to underrate it, but I'm here to help!

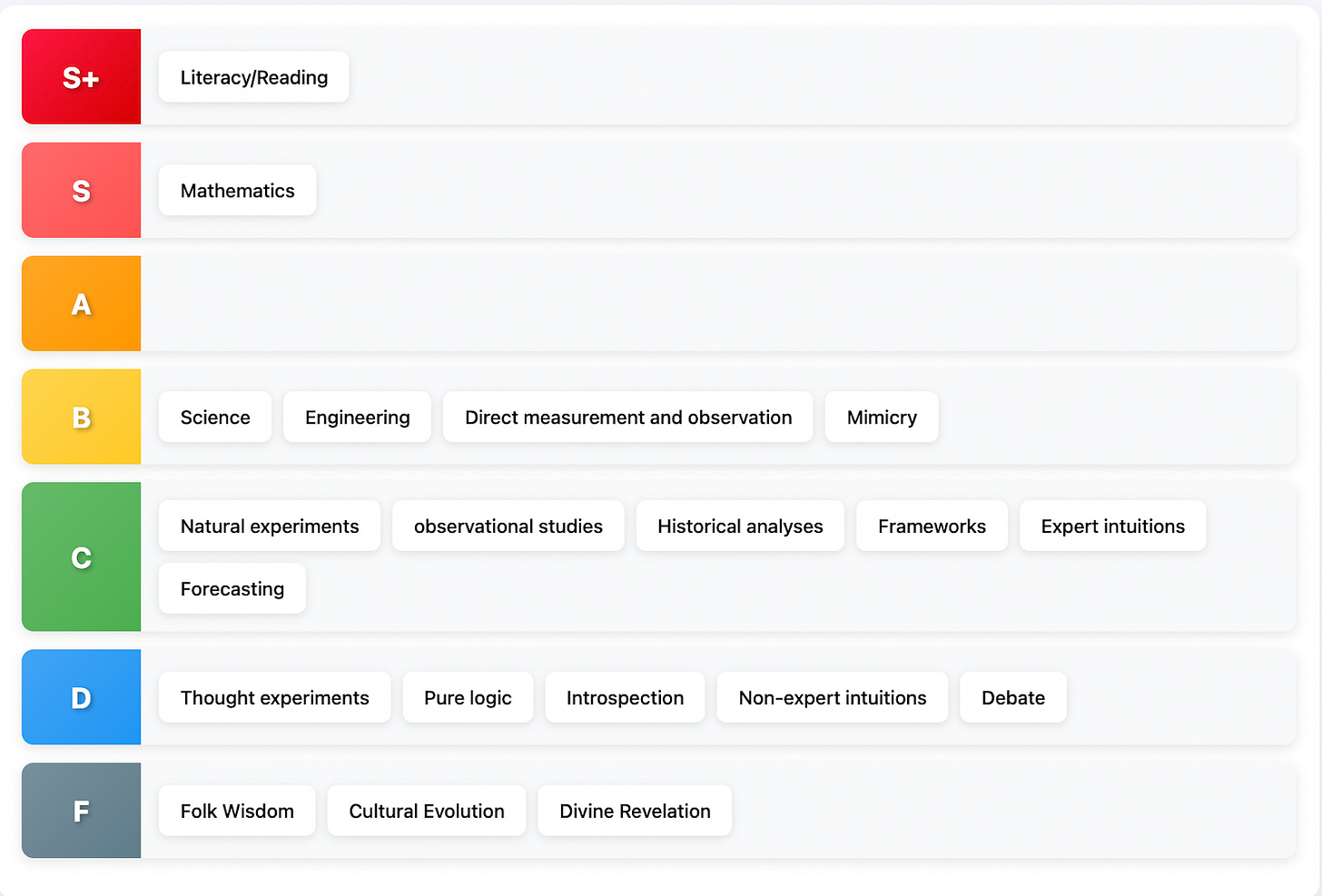

New-ish substacker Linch Zhang at The Linchpin has a fun post that ranks the “ways of knowing,” which he summarizes in this tier list:

The first thing I noticed is that it’s strange to rank things like “reading,” “science,” and “non-expert intuitions” in the same list, but having thought about it, it kinda makes sense. We might consider the elements in this chart as answers to the question, “If I want to know something, what techniques can I use?”, conflated with answers for “How does human civilization produce new knowledge?” This conflation makes things a little confusing, but the list is interesting nonetheless.

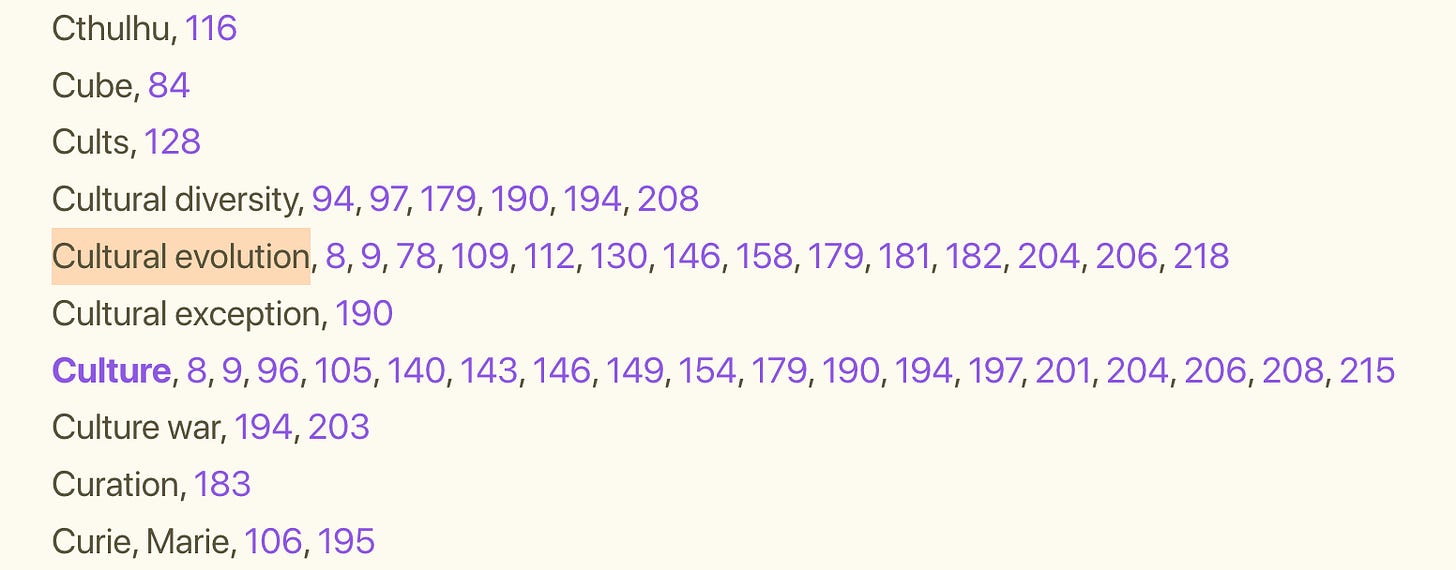

The second thing I noticed, because this is a topic I know well, is that cultural evolution is ranked very low, on par with folk wisdom and divine revelation.

Broadly speaking, cultural evolution is the application of evolutionary concepts from biology, like mutation and natural selection, to cultural traits. These traits cover any type of information that is socially transmitted: ideas, customs, styles, technologies, non-innate behaviors, etc. “Evolution” means the way this information changes over time, driven by mechanisms like innovation (analogous to mutation) and cultural selection (analogous to natural selection, i.e., how we choose to keep certain cultural traits and not others, and accumulate them).

Cultural evolution can be said to produce new knowledge, but Linch finds it unimpressive. In his list, “literacy is ranked highly . . . because it delivers extraordinary returns on humanity's investment compared to, say, cultural evolution's millennia of trial and error through humanity’s history and pre-history.” He adds that “cultural evolution (F tier) is vastly overrated.”

I’m really curious about who, exactly, is doing all this overrating, since I hold the opinion that cultural evolution is vastly underrated. In fact, it’s often not rated at all: most people aren’t even aware of it. It’s surprising to see it on the chart, to be honest. But once we assume the writer knows what cultural evolution is, it’s even more surprising to see it ranked in the “Fail” tier.

Here’s how Linch justifies it:

Let's be specific about cultural evolution, since Henrich's The Secret of Our Success has made it trendy. It's genuinely fascinating that Fijians learned to process manioc to remove cyanide without understanding chemistry. It's clever that some societies use divination to randomize hunting locations. But compare manioc processing to penicillin discovery, randomized hunting to GPS satellites, traditional boat-building to the Apollo program.

Cultural evolution is real and occasionally produces useful knowledge. But it's slow, unreliable, and limited to problems your ancestors faced repeatedly over generations. When COVID hit, folk wisdom offered better funeral rites; science delivered mRNA vaccines in under a year.

The epistemic methods that gave us antibiotics, electricity, and the internet simply dwarf accumulated folk wisdom's contributions. A cultural evolution supporter might argue that cultural evolution discovered precursors to what I think of as our best tools: literacy, mathematics, and the scientific method. I don't dispute this, but cultural evolution's heyday is long gone. Humanity has largely superseded cultural evolution's slowness and fickleness with faster, more reliable epistemic methods.

There are several confusions here — starting with the fact that the Fiji example in The Secret of Our Success isn’t about manioc, but about taboos on eating shark while pregnant. The manioc example is from Amazonia! But okay, minor mistake, it doesn’t matter to the argument. There are bigger issues, and looking at them will help us get a much clearer picture of what cultural evolution is and why it matters.

The #1 problem in Linch’s post is his implicit definition of cultural evolution. It’s not exactly wrong, but it’s too strict. He suggests that cultural evolution takes “millennia of trial and error,” and that it is “slow, unreliable, and limited to problems your ancestors faced repeatedly over generations.” None of this is true, except the trial-and-error part. Cultural evolution does operate by trial and error, but that can happen far faster than generations or millennia, and it’s not particularly unreliable, since we can control the selection mechanism in many cases.

Here are some toy examples at various time scales, with different ways to perform the trial-and-error step and the selection step:

Centuries and millennia: Chimpanzees try to eat termites by digging in termite nests with their hands for 100,000 years. Then one chimp randomly pokes a nest with a stick and discovers that she can get termites more efficiently this way (trial and error). Later, another chimp sees the first chimp do it and be rewarded with many juicy termites, and imitates the behavior (selection). The knowledge of using sticks slowly spreads, but it takes hundreds of years for the entire population to adopt it.

Decades or generations: The manioc story. Various tribes of the Tukanoan people in the Colombian Amazon eat manioc, a.k.a. cassava, as their staple food. Manioc causes cyanide poisoning in the long term, but you don’t notice it with either sight or taste, and without modern science, it’s basically impossible to link manioc to disease. One tribe randomly has this habit of waiting two days before eating the manioc fiber, which detoxifies the manioc, though they don’t know it; another just eats it immediately (trial and error). Over a few decades, the members of the first tribe are overall healthier, allowing them to reproduce and survive better, while the tribe that doesn’t detoxify eventually goes extinct (selection).

Years: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is messing around at his keyboard (trial and error), and invents a new kind of musical flourish in one of his symphonies. He publishes the symphony. Other up-and-coming composers find it cool, and within a few years, they also use the technique in their works, changing the course of classical music history (selection).1

Months and weeks: Dozens of SaaS startups get founded in the AI space, taking advantage of recent LLM advances. They experiment with various projects (trial and error), and within a few weeks, some of them start getting traction since they fill a user need (selection).

Hours and minutes: Thousands of people post jokes and hot takes on Twitter, most of which are bad and boring (trial and error); but every once in a while, one of them becomes viral because it’s particularly funny, interesting, or egregious, which encourages people to share it further (selection).

Sometimes, of course, the selection step is a totally uncontrollable, even unnoticeable phenomenon, as in the manioc story. But many other times it occurs through rational human behavior, such as users buying SaaS or choosing to retweet something they like (or dislike). The trial-and-error step can also be controlled to some extent: Mozart or startup founders can deliberately choose to experiment, or even induce creativity using specific techniques or substances.

What happened in Linch’s post, I suspect, is that he overfit on the examples in Henrich’s book. Henrich is an anthropologist, and most of the evidence he describes comes from studies of hunter-gatherer societies, humans vs. great apes, and child psychology. This makes sense for a field that tries to encompass so much (many things are cultural!) and yet is still fairly young (a couple of decades). You’ll make more progress if you study the mechanics of human culture at the boundary between humans and other animals, without the confounding effect of the layers and layers of culture that make up the life of an adult in a complex modern civilization. But the idea generalizes far beyond anthropology.2

A related error in Linch’s post is to consider cultural evolution as distinct from the other ways of knowing in the list.

It would be both boring and useless to claim that all of the items are examples of cultural evolution. To be sure, you certainly could make this argument: In a broad sense, cultural evolution covers almost every kind of knowledge process used by humans, with the exception of the knowledge encoded in our genes. But some of the items in Linch’s list are more closely associated with it than others. And those few items, in fact, cover most of it. I don’t know what’s left if you take them out from under the cultural evolution umbrella.

First, folk wisdom. Also rated as F-tier. Cited twice in Linch’s three paragraphs on cultural evolution (“The epistemic methods that gave us antibiotics, electricity, and the internet simply dwarf accumulated folk wisdom's contributions”). It’s unclear to me what the distinction is here. Maybe the idea of accumulation? But folk wisdom without accumulation doesn’t really make sense; isn’t the point of folk wisdom that it has been transmitted across generations? Otherwise it’s just random life advice by an elderly person. It seems that Linch conflated the two concepts and should have just merged them into one, called “folk wisdom” or maybe “culturally evolved folk wisdom.”

Second, mimicry. B-tier: one of the better ways of knowing, according to the list. But if you read The Secret of Our Success, you’ll realize that this actually is the main mechanism of cultural evolution. A successful hunter gets imitated by younger aspiring hunters. Toddlers learn about the world by imitating their parents and older siblings. A core argument from Henrich is that humans are particularly good at transmitting cultural information in this way, unlike chimps and other animal species.

Third, expert intuition, classified as C-tier, and non-expert intuitions, D-tier. We humans are good at mimicking and learning, but not from just anyone. Henrich describes various quirks of human psychology that help us identify experts, or at least the most successful individuals in a particular task. This is why we’re sensitive to prestige: it’s an (imperfect) signal of expertise. So Linch’s two items on “intuition” are clearly part of cultural evolution: figuring out who to pay attention to is a key mechanism.

Fourth, literacy/reading. This is Linch’s top way of knowing, at the S+ tier. Literacy certainly isn’t needed for cultural evolution to occur, but boy, does it help with the accumulation part.

Fifth, social media, ranked as F--. For what it’s worth, I don’t fully agree that this is the absolute worst way of knowing, but regardless, it’s a clear example of trial and error and selection, as seen in my earlier Twitter example.

The other ways of knowing can also be massaged into fitting within the cultural evolution frame. Science, for example, definitely also works through trial and error, followed by selection of the best knowledge through criticism. Indeed, there are epistemologists like Karl Popper who argue that all knowledge production is evolutionary. But even if we don’t go all in, notice how the items I picked cover the full spectrum from F-- to S+. This makes it pretty hard to decide in which tier to actually put cultural evolution, if we wanted to update the list…

… which brings us to this question: should cultural evolution even be in the list at all?

In some sense, sure, it’s a way of knowing. But unlike the other items in the tier list, it’s not really something you choose to do. Most of the time, it just happens: knowledge gets created and selected, and has thereby evolved. And to the extent that you can choose to do it, by deliberately innovating and selecting, that’s an indistinguishable process from most other ways of knowing.

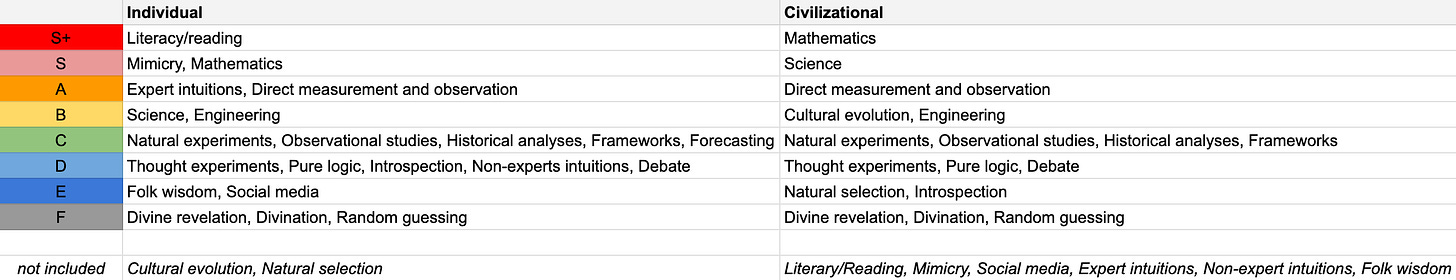

If I wanted to make a better list, I would split it in two, removing the conflation I mentioned earlier. One tier list for the question, “If I want to know something, what techniques can I use?” and another for “How does human civilization produce new knowledge?” Literacy would appear in the former, but not in the latter, since it’s not possible to produce knowledge new to humanity just from reading (at least until we meet literate aliens). Cultural evolution wouldn’t be in the former, but would show up in the latter, probably ranked somewhere in the middle.

For that matter, Darwinian biological evolution should be in the latter list too, ranked lower than cultural evolution. Mutation + natural selection does produce new knowledge, encoded in DNA. It’s a very lousy way to learn, it takes millions of years and it generally involves killing off every organism that makes a mistake, but it works.

I made this very quickly and didn’t put that much thought into each individual item, but here’s what my two-part list looks like:

I learned about cultural evolution when I happened to be a research intern in Joe Henrich’s lab at Harvard for half a year, back in 2016, which is also right after The Secret of Our Success was published. Ever since, I’ve been puzzling over why the idea is so little-known and often misunderstood.

Part of the answer might be that it’s surprisingly counter-intuitive, like biological evolution by natural selection. The mechanism is simple, but it’s difficult to grasp that complex living things or complex cultural traits evolve out of mutation and selection, without any sort of goal-oriented (teleological) processes.

In addition, cultural evolution is more complex than biological evolution, because it operates along more mechanisms. In biology, the information is stored in a standardized way, in genes. Genetics certainly is complex, but it’s tractable. Also, in a sexual species, genes are passed to a new organism almost exclusively when two organisms reproduce. (There are exceptions, like horizontal gene transfer, but they’re rare in complex organisms like animals and plants. We can also do this artificially with genetic engineering.) By contrast, in cultural evolution, the equivalent of a gene, the meme, is very poorly defined. This has prevented memetics from establishing itself as a formal field. And memes can spread in a multitude of methods, including sexual reproduction (parents passing their behaviors and values to their children), but also education, media, the influence of friends, etc. Not to mention that there are different levels of memes that interact in various ways: whether a group adopts the cultural practice of eating shellfish may be influenced by the “larger” cultural practice of being Jewish.

But in another sense, cultural evolution might still be underrated simply because it hasn’t been written about that much. It’s a young field, and it might still be difficult to tease the ideas apart from the few mainstream books, papers, and blog posts that have been published on the topic. Which is why I’ve been writing about it often, though rarely as the main idea of a post.

I’ve been meaning to write about it more formally several times, and for some mysterious reason I find it very difficult. So I’m happy I got to leverage the motivation of proving someone wrong. Hopefully Linch appreciates that this, too, is cultural evolution in action. A substacker writes about cultural evolution in a mistaken way (trial and error); another critiques the problems in it (selection); we collectively arrive at better knowledge. It’s not the worst way to make progress!

This is my 3rd Roots of Progress Blog Building Intensive post! Thanks to Linch Zhang for providing the fuel, to Venki for drawing my attention to Linch’s post, to BBI fellows Steven Adler, Hiya Jain, and Andrew Burleson for feedback, and to Mike Riggs for editing.

Example loosely inspired by the discussion of “selfish embellishments gestures” in Mozart the Performer, by Dorian Bandy, p. 157-160:

An analogy with evolutionary theory suggests itself: “selfish” embellishment gestures, the cellular constituents of Mozart’s melodic style, replicate continuously, with successful variants spreading throughout subsequent thematic reprises or even entire compositions. . . . Many features of Mozart’s embellishments would, shortly after his death, come to define the musical vernacular in the first part of the nineteenth century.

To be fair to Linch, I’ve also defined cultural evolution this way before. I was rereading this post about ethics, and wrote that

cultural evolution is a major, if not the main force in explaining human behavior, by encoding extremely complex norms through adaptation over generations.

Overfitting to generation-scale examples is really easy to do!

"The first thing I noticed is that it’s strange to rank things like “reading,” “science,” and “non-expert intuitions” in the same list, but having thought about it, it kinda makes sense. We might consider the elements in this chart as answers to the question, “If I want to know something, what techniques can I use?”, conflated with answers for “How does human civilization produce new knowledge?” This conflation makes things a little confusing, but the list is interesting nonetheless."

Thank you for agreeing it's interesting! :P In case you're curious, the main impetus for writing the post is that I wanted a "non-foundational foundation" on how to view the world[1]. There are many reasons for this, but one is to showcase how an analytic, scientifically-minded person might attack "scientism" (or other modern flavors of trying to systematize everything, like Bayesianism) without becoming postmodernist or otherwise nihilistic about science and truth.

I think a common failure mode of systematization is taking a specific way that people successfully seek truth (eg the scientific method, or Bayesian updating) and try to argue that all other methods of belief formation are just bastardizations of the better method. I think this is wrong-headed and confused. Which is why I tried to improve on it!

This is also why reading was on the top of the tier list, in addition to being what I object-level believed. Because nobody (except maybe a few theologians) would take seriously the idea that the only way to seek truth is through reading.

I was pretty disappointed by the reception of the post after writing it. It was one of my worst-performing posts initially (in terms of early views and likes), and it was panned on LessWrong and r/philosophyofscience (which liked an earlier post of mine).

But over the last month, I noticed a steady stream of new views on the post, it's gotten positive reception in private comments by subscribers and people I respect on these issues (eg academic epistemologists), and now there's an entire high-quality substack post critiquing it! So I'm going to reserve judgment on whether the post failed for now.

Thanks again for the critique!

[1] Here's an earlier version of the intro that I decided to not include in the main post because it was too long and too genealogical:

"How do you reach true beliefs about the world? Here's how I do it:

I'm born. I look around the world. I try to form true beliefs. I use a variety of methods to form true beliefs, and I try my best to reach consilience between them. As I change my beliefs about the world, I also change my degree of trust in different methods that can arrive at such beliefs. (When I use a ruler to measure a table, I'm learning more about both the table and the ruler)

I think what I said above should be extremely unsurprising! You almost certainly use a very similar method, consciously and otherwise, to form beliefs and opinions, change your mind, and make day-to-day decisions.

Yet I think people often tie themselves in knots when thinking about "epistemology" or how they know things. People talk about the scientific method, or AIXI and/or Bayesian Decision Theory, or some other extreme formalism, as if that's how they actually form beliefs or make decisions! Or they have a form of extreme methodological pluralism and take a "who's to say, man?" attitude about which methods are right, as if all methods are equally "valid!"

Or worse, they reject truth altogether! (Which is a fun conceptual lens for a few days, but a poor way to live life!)

"

I like this breakdown of knowing, between the superorganism (cultural groups) and its nodes (individual people). Surely our lower levels of abstracted organization also have their own way of learning, whether it’s our immune system reading and recording the genetic signatures of infectious diseases, or something more subtle that the rest of our cells do which we file under the broader category of “trial and error” or biological feedback loops. Natural selection happens at all scales - a taxonomy of its specific mechanisms is definitely a fruitful chain of curiosity.