We Need Polycentric Cultures of Progress

Progress studies must eventually expand to countries outside the Anglosphere

The progress studies movement is young, and like most young things, has a lot of potential for growth. But to make the most of it, it will have to escape its current monocultural focus.

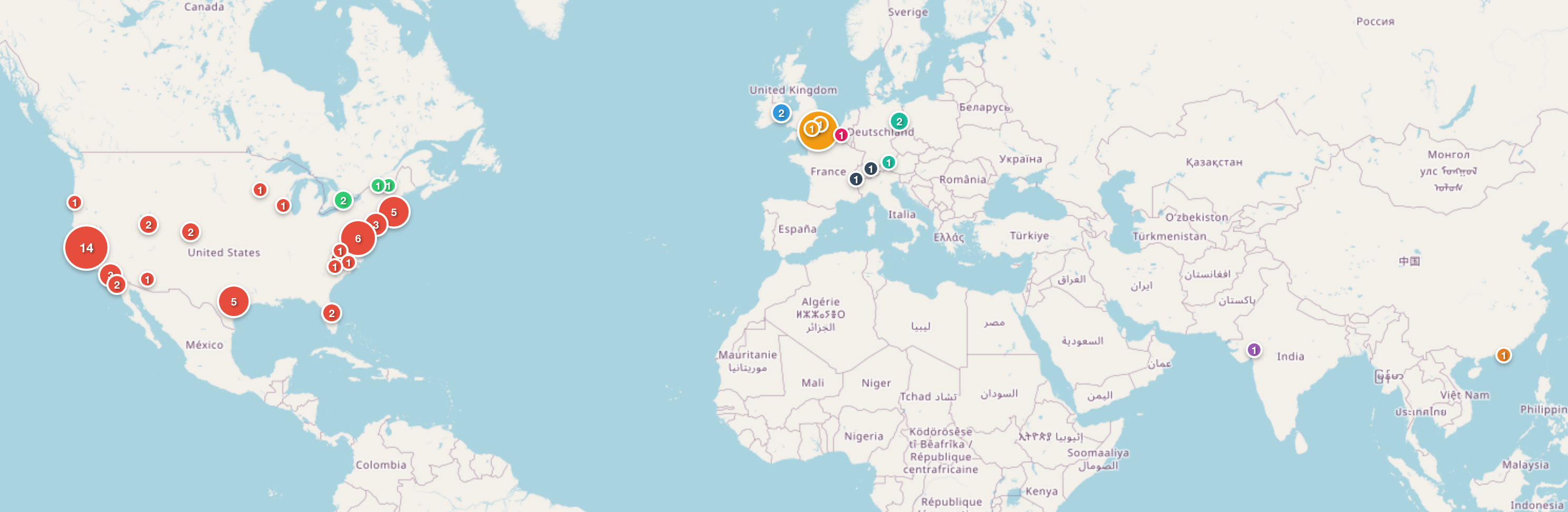

To illustrate what I mean, consider the Roots of Progress Blog-Building Intensive, hereafter BBI, which is the program I have been lucky enough to be in the past few months. It is now reaching the end of its third year. There are 31 of us in this cohort; there were 24 and 19 in the first two, for a total of 74 fellows. Everybody (with one exception) says where they’re based on the fellows’ web page, so I collected the data and vibe-coded a little map showing our geographical distribution.

To the surprise of nobody, most fellows — more than 50 — are based in the United States, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, with strong contingents from Washington, D.C., Boston, and Austin. (Surprisingly few people in NYC, only 3.) The rest of the Anglosphere, at least the part in the Northern Hemisphere, isn’t too poorly represented, especially London, with 7 (the number is hidden on my quickly put together map by our representatives from Cambridge and Oxford). There are also a few fellows in Ireland and Canada.

Outside of that, the German-speaking world has a few representatives in Germany and Switzerland, Maarten Boudry hailing from Dutch-speaking Belgium, and we have one fellow each in India and Hong Kong. And then there is myself, in French-speaking Canada — perhaps technically the Anglosphere, but not really.1 Nothing from France, Italy, Scandinavia, Japan, Australia, the entire Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking world, all of Africa, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, or the Middle East.

None of this is particularly surprising. The BBI is in English, so of course it’s going to primarily attract English speakers. In fact, it selects for advanced English speakers who are excellent writers in that language; this is definitely going to be skewed towards educated people in rich Anglo countries. Then the BBI is based in the United States and run by Americans, with a schedule that is suited best for people in the Western Hemisphere. More broadly, the progress movement is one of those many Silicon-Valley-adjacent subcultures, which makes it particularly present in the hubs of the American tech industry, chiefly among them the San Francisco Bay Area (but also places like Austin, Texas). Progress studies has its intellectual origins in thinkers like Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison, who have ties to the Washington, D.C. area, the SF Bay Area, and Ireland.

Nor is any of this particularly problematic. The United States is the world’s cultural superpower, it’s huge, it’s dynamic. It makes sense that new political movements sprout there, just due to the sheer number and talent of the people who live there, whether by accident or by choice. And it makes sense that those movements primarily try to change the United States, whether through policy or by influencing the US’s massive technological industry. At the scale of the world, English is the lingua franca; many people speak it, and it attracts the smartest people, the ones most likely to come up with the next big idea. If you want to spread such an idea, you’ll write it in English; otherwise, you handicap yourself for no reason. Even if you just want to write as a hobby, it is much more rewarding to do it in English, as I discovered years ago. And if you want cultural diversity, there definitely is a lot of it within the mostly Anglo and American group of the BBI fellows: some come from China, Iran, India; some have a background in AI, agriculture, policy, and health. It’s also very common for progress people to research and write about what is going on all over the world (e.g., from sampling Works in Progress, on French nuclear power, on the Madrid metro, on Japanese urbanism).

So the fact that the BBI is US- and English-centric isn’t surprising or problematic. Why, then, am I writing about it? Because it suggests an opportunity.

Ultimately, the goal of the progress movement is to further the welfare of humanity. It is not to assert the dominance of a single country. Sometimes incarnations of the movement take a patriotic guise, like Anglofuturism or American Dynamism, but even if you were motivated primarily by nationalism, it would benefit you and your country to live in a dynamic world where other countries are excellent trade partners and the source of innovations you can borrow. Most progress people believe, rightly, in the benefits of free markets and the free flow of ideas.

But even in non-US/UK Anglosphere countries, the progress studies movement is barely getting started. (The only Canadian progress-adjacent organization I know of, Build Canada, was founded earlier this year.2) In non-Anglo countries, almost nobody has ever heard of it; at least that’s my understanding of the cultural sphere I’m in, the French-speaking world. If you’re from a country that isn’t the US or the UK, or have cultural or linguistic links to such a place, you can have a large impact there, and make the progress movement benefit a larger fraction of the world.

One problem with this is that it’s very hard. If you already have an established audience in English, writing in your other language is almost tantamount to starting from scratch.3 I used to write in French, with painfully slow growth, and I was almost immediately rewarded when I switched to English, due to network effects, a larger pool of readers, and a larger pool of reader subcultures.4 I routinely dream of taking up writing in French again, because I want to influence the culture and politics of where I live, but shouting into the void again, as new writers do, is very unappealing. The lack of any sort of progress culture here, which is the problem I would like to solve, paradoxically makes it even harder to make the switch. So I’m defaulting to a strategy of slowly becoming established in English, which hopefully transfers in some measure to French later on. I don’t know if that will work.

Sometimes I tell myself, or hear from others, that it is just not worth doing. It’s more effective to contribute directly to the central, bigger, more advanced movement that is growing in the Anglosphere. Eventually, there will be cultural diffusion as the movement becomes too big to ignore. The premier of Quebec was reported in the news to be reading Abundance by Klein and Thompson, which I suppose is a good sign.

But diffusion can be slow, and time matters. Every year that a European country follows some bad degrowth policy is a year with less technological development, less wealth, less trade with other countries, less human welfare. Besides, someone has to do the diffusion. Why not you, young progress writer?

Beyond the impact on those countries themselves, I also think — and this is a drum I keep beating — that cultural diversity is extremely important. Sustained progress depends on not putting all our eggs in the same basket of a single monoculture. Things naturally tend to cluster: the tech industry in San Francisco, for example. This is risky in subtle ways. The elite of the tech industry might become detached from the rest of the world, too focused on concerns that make sense only in San Francisco. Likewise, if the progress movement remains too American or Anglophone, it will quite possibly miss a lot of the good it can do in the rest of the world, and limit its reach. There certainly are a lot of people who will be much more amenable to progress ideas if they see it as a homegrown thing rather than a foreign American concept.

Historically, Western civilization has advanced rapidly, in part thanks to decentralization: different countries pursuing different objectives and competing with one another. This was true in the Greek city-states; in the republics and duchies of Renaissance Italy, or the countless statelets of the medieval German world; among the early modern European powers such as Spain, Portugal, France, and England, and then between their various colonies; and in the federalized states of America. Some of the most successful movements in history have taken advantage of this: consider the extensive international reach of Christianity, or communism, or environmentalism, all of them spreading over the years in myriad local variations across the world.

It will be hard to do, but it’s time for us in the progress studies movement to think seriously about how we will create many cultures of progress, instead of just one.

This is an essay I’ve been meaning to write for a long time, and I would like it to serve as a call for action. I’m trying to figure out how I can do some of that work myself in Canada, Quebec, and the French-speaking world, so if you’re interested in contributing, teaming up, or just providing words of encouragement, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

I’m also very interested in hearing from anyone who has had similar thoughts from other countries or cultural spheres. If you feel like you’re the only one in your country who cares about progress, let’s talk!

Big thanks to Andrew Burleson and Mike Riggs for feedback. This was my 4th BBI fellowship essay. By the way, I’ll be at the Progress Conference 2025 this week! Come talk to me if you’re there!

There is another fellow from Quebec, Jeremy Côté. He told me he’s mostly English-speaking, making one of the few remaining Eastern Township anglophones.

I happen to have attended their Montreal meetup on October 9th. It was at the Montreal offices of Shopify, and it involved a fireside chat between the founder of Build Canada, Lucy Hargreaves, and one of the cofounders of Shopify, Harley Finkelstein. Finkelstein did most of the talking and was quite inspirational. It was all very entrepreneurship-focused, and optimistic, and it made me want to get more involved in the Montreal policy and/or tech scene.

Not totally, because you can borrow the intellectual materials from your own English-language writing practice and other people’s, and because the experience and a small fraction of your existing audience can transfer, but it’s still a big step back.

By subcultures, I mean a broadly defined set of things like writing groups, specific publications, the commentariat on specific publications Astral Codex Ten, fellowships like the BBI, movements such as rationalists, effective altruists, and progress studies, social media clusters like This Part of Twitter or Substack, and also something even more vague than all that, “culture” in the sense of the emerging characteristics of any group of people that share something in common. There is more of all that in English just because there are more English-speaking readers of blogs.

What's funny is its not even representative of western culture. I'm in Nashville, and like with many intellectual pursuits the middle of the US is often overlooked. It's more of an ideological likeness though, I suspect. Movements shrink up and tend not to venture too far away ideologically. That's how these NGOs work. They need coherence. Not sure how to fix that, but this is why I don't apply to a lot of things unless I know the leaders personally. You have a snowballs chance in hell if you don't align perfectly with their goals.

Hello Etienne, I have been following your writing since the french blog. I live in Quebec, in a 95% french environment but your ideas still reach me, so that's the counterpoint I'd like to expend upon.

In order for ideas of the anglophere to diffuse beyond, there seems to be two big vectors: authors who evangelize in the non-english language, or simply more people who read English.

In every language, there are people with big audiences for that language. However, the size of the potential audience seems to limit how niche your subjects can be before they find almost no-one. The logical conclusion is that the local language evangelizing is best done by people who already have a big general audience. But these will want more surface level and widely appealing messages.

English is now the linga franca of international discussions. People who gravitate towards niche subjects like, say, beating Mario 64 with very few A button presses, will find it rewarding early on to participate in the anglosphere. That of course leaves behind lots of people for which the barrier to entry is high. The conclusion to me seems that the best way for ideas to diffuse globally is through more people learning English easily, to lower that barrier.

A downside is that this kind of mono-culture will be more homogenous than if the ideas are planted in isolated cultures and allowed to develop more independently with the barrier of language. But that seems a bit unavoidable if the goal is for ideas to reach all the participant pool.