Reality Will Become a Status Symbol

AMW #53: On the metaverse, reality privilege, and owning a nice house in worlds both virtual and physical 🏡

The Greek prefix meta– means “after,” “beyond,” or “to transcend.” Facebook, the behemoth of social media, recently rebranded itself as Meta Platforms, Inc. Facebook is going to transcend reality. It’s going to build the metaverse. Or so it claims.

Nobody really knows what the metaverse is supposed to be, exactly. It’s a buzzword. But to the extent that it means something, it’s some sort of improved and combined version of what currently exists in the form of:

social media

video games, especially massive multiplayer online games

virtual reality

augmented reality

crypto and web3.

One of the features of the metaverse that doesn’t quite exist yet is a form of persistence between all of the above. Right now, we have a bunch of separate platforms like Facebook, Twitter, World of Warcraft, Animal Crossing, Second Life, and so on. The only thing that links them together is the users’ physical identities. The metaverse, by contrast, promises that you will be able to move between platforms while retaining your digital identity. It is a new universe, parallel to the physical one, “transcending” it.

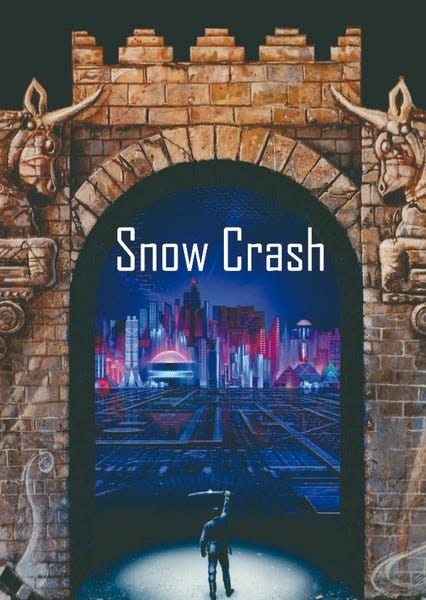

The metaverse is also a staple of science fiction. It is often associated with the 2011 book Ready Player One, which I have yet to read; I compensate this inadequacy by having read Snow Crash twice.

Snow Crash is a novel from 1992 by Neal Stephenson, and the origin of the word “metaverse” itself. In Stephenson’s vision, the Metaverse is a virtual planet that people access through VR headsets. The Metaverse is populated with users who walk around wearing avatars that may or may not be realistic; it has a real estate market, and there are private properties and exclusive clubs. The hero and protagonist of the book (who, in Stephenson’s silly, satirical style, is literally named Hiro Protagonist) lives in the crappiest environment in reality, a self-storage business converted to cheap apartments near the Los Angeles airport. But in the Metaverse, he owns a nice house. He carries awesome samurai swords. And he has a good reputation from helping code the virtual world. In the Metaverse, Hiro Protagonist is far cooler than he is in real life.

Hiro Protagonist is a cartoonish but prescient version of a real phenomenon: online escapism. His reality isn’t great, so he takes refuge in the metaverse as often as he can. In our world, this manifests through, for instance, video game and social media addiction.

There’s something that makes me, and many others, uncomfortable with the idea of escaping reality for most of our waking hours. But on some level, it’s understandable. Most people don’t live in amazing realities. Most people live in poor countries or bad neighborhoods. They can’t afford to travel to wonderful real places. They don’t have large beautiful houses full of art and cozy furniture. They might have a shitty social graph, suffer from loneliness, live with abusive family members, and so on. So they escape to the online world: they post incessantly on social media, they play MMORPGs, they get involved in Discord servers where they find friends and meaning.

Marc Andreessen, the a16z guy and one of the original inventors of the web browser, summarizes this idea under the concept of reality privilege. The phrase has stuck in my mind ever since I read it in the interview where Andreessen defines it (emphasis mine):

A small percent of people live in a real-world environment that is rich, even overflowing, with glorious substance, beautiful settings, plentiful stimulation, and many fascinating people to talk to, and to work with, and to date. . . . Everyone else, the vast majority of humanity, lacks Reality Privilege — their online world is, or will be, immeasurably richer and more fulfilling than most of the physical and social environment around them in the quote-unquote real world.

Now, I certainly am a reality privileged person. Chances are that you are too, since I expect readers of this newsletter to be of a similar social class as I am. If you’re like me, you… won’t really like the concept of reality privilege itself. And you won’t like Andreessen’s conclusion that we should focus our efforts on building wonderful online worlds — the metaverse — because most people will never get to experience reality in its full overflowing glorious substance.

But such criticism isn’t new to Andreessen. In fact, he says, it is a pretty clear sign of reality privilege to even criticize the idea. “A visceral defense of the physical,” he quotes from Beau Cronin, “and an accompanying dismissal of the virtual as inferior or escapist, [could be] a result of superuser privileges.” If reality looks beautiful and stimulating to you, it’ll seem mistaken to build an escape hatch — but the escape hatch might be exactly what those who don’t share your perspective want.

I want to stress that I really dislike this idea. It repulses me. And yet I can’t shake the feeling that it’s correct. Building the metaverse could improve the lives of millions or even billions. It may not be the best way to improve their life, but if it’s an improvement, who are we to say no?

This tweet describes the resulting ethical dilemma pretty well:

Obviously we’d prefer to make physical reality wonderful for everyone. But that’s costly and difficult. What if most people can’t get that? Is it good to partially escape misery if it prevents you from totally escaping misery? I have no idea what the answer is! It’s so confusing! Gaaah!

One not-so-satisfying way out of the dilemma is to dismiss it. Whether you or I think it’s a good thing, the metaverse will happen. Meta Platforms, Inc. is working on it. Video game studios and VR and AR companies are working on it. A good chunk of the crypto/web3 world is working on it. Even if we don’t fully recreate Snow Crash or Ready Player One (and I certainly hope that we don’t), the online experience will keep getting better. As a result, it will absorb more and more of people’s time. What happens then?

Many things happen then, but one of them is the prediction that I chose as the title of this post. I claim that in the near future, spending most of your time in physical reality, as opposed to online or virtual reality, will be a sign of wealth and status.

It seems to be a non-obvious prediction. I have seen hints of it in some places, such as this post by Caseysimone, which suggests that as media stimulation becomes ubiquitous,1 “Calm and the un-augmented will increasingly be for the rich.” But to my knowledge, the idea of reality as a status symbol doesn’t get discussed a lot.

I think it’s in part because the metaverse is a new and shiny idea, so right now, it is a status symbol, at least in tech circles. Once, I spoke of this prediction to a bunch of crypto friends. I claimed that we were all reality privileged — which was pretty obvious to me, considering that we were enjoying a nice campfire in a gorgeous piece of Texas countryside. My friends didn’t seem to agree very much, or perhaps they didn’t want to agree. If we’re reality-privileged, why are we building the metaverse? one of them asked.

Yet I am quite confident about my prediction.

There is some evidence from tech executives limiting the screen time of their children, for instance. You might expect tech exec households to use tech more than normal people, but that would be forgetting that, as some of the wealthiest people in the world, they have extreme amounts of reality privilege. They can afford to live amazing lives with a moderate amount of time spent online, and they do.

As the metaverse grows, this phenomenon will only get more salient. Virtual reality will offer you an immersive visit of the Parthenon that’s almost as good as the real thing. This will reduce the value of actually flying to Athens to discover the Parthenon, since there wouldn’t be that much more to learn and see that way. But those who fly to Athens anyway will be seen as really high status: they’re spending a lot of money for little gain!

It makes sense. Status symbols derive their strength from two things: being difficult to obtain, and/or being somewhat wasteful. A $3000 Louis Vuitton handbag is a sign of status because very few people can spend this much money on something as mundane as a handbag. A Nature paper is a sign of status because very few scientists manage to publish in Nature. A Harvard degree is a sign of status because very few people manage to get into Harvard and can afford to spend four years studying Celtic literature of whatever.

The metaverse will make it easier to get certain things virtually compared to getting them physically. It will make it seem wasteful to get those things in physical reality. The predictable outcome is that getting those things in physical reality will become even more impressive.

What is higher status: having a gorgeous house in Animal Crossing, or having a gorgeous house in real life?

Of course, having a nice house in Animal Crossing, or a nice pair of katanas in the Metaverse of Snow Crash, or a dope collection of NFTs on the Ethereum network, does have some value. It’s higher-status than not having those things, at least among peers (e.g. Animal Crossing players or crypto people). So I’m not saying that everything online is going to be low status. Quite the contrary! The metaverse will create new status hierarchies. The sale of digital art through the NFT mechanism is an interesting (and early) foray into that: NFTs use blockchain technology to create artificial scarcity, so they enable ways for people to acquire and display their status within the crypto community.

But at the scale of human society, those things will have lower status than being wealthy enough to afford comfortable and rich physical homes, to buy and display physical works of art, to travel the physical world, and to meet cool people in person.

Another thing I’m not saying is that wealthy people will altogether avoid the metaverse. Wealthy people come in all shapes and forms, and many of them are and will be, like Mark Andreessen, tech enthusiasts. Many will spend a lot of time in the metaverse because they like it for whatever reason. Yet I suspect that even tech-friendly rich people will also spend their money to raise the quality of their physical life. And then there’ll be wealthy people who do avoid the metaverse — something that will become increasingly difficult to do for poorer people.

Lastly, I’m also not saying that ascribing high status to physical reality is either right or wrong. You’re totally free to reject that idea and consider the metaverse higher status if you like, or, conversely, to revel in your reality privilege and scoff at the online/AR/VR addicts. I don’t care. I simply predict that society as a whole will care, and will choose the latter more often than we currently think.

Well — at least for now. It seems possible that the metaverse becomes extremely high quality on a longer time horizon, with highly immersive haptic experiences, or perhaps even full simulations that you permanently plug into, Matrix-like. In such a scenario, the metaverse could be said to be strictly better than physical reality in some sense: it would be well-made enough that it wouldn’t feel lacking, while it would allow a variety of experiences that are impossible in the real world (say, flying with your own body). Maybe, then, it will win the status war against reality.

However, that’s a long way off, and I wouldn’t bet on it, even if Facebook et al. have begun crafting the building blocks of the universe beyond our own.

For now, we should make sure that our attempts at transcending reality end up improving people’s lives more than they harm them. And we should consider the metaverse as just a backup plan: it’s far better to improve the physical world itself, even if it’s costly. Let’s not leave all of reality to a minority of well-off people.

Post-Scriptum

I launched jawws.org this week, a simple website for my science communication project. Right now it mostly contains a list of resources related to readability in science, the state of science publishing, etc. Feel free to visit and share it.

You can subscribe to Atlas of Wonders and Monsters here:

This is a prediction made, among others, by Erik Hoel in this Intrinsic Perspective post about the year 2050. Note that 2050 is in 29 years, exactly the same distance that separates us from Snow Crash in 1992.

this was really good food for thought, specially because i'm highly tech/online enthusiast. the dilemma rings :)

Whenever someone splits people between low-mid-high this mental image pops up from Venkatesh Rao contra Maslow. Small minds of the working class care about people (immediate survival), average minds of the blue collar middle class care about events (long term safety), middling minds of the white-collar middle class care about institutions (belonging), sub-optimal minds of the professional class care about markets (self-esteem & understanding), great minds of the upper class care about ideas (aesthetics & fulfillment). https://archive.ph/xQ54z https://archive.ph/LnVKu

If this is true, belonging and solidarity (and in a lesser sense good self-image & psychological security) would be the crux of making reality tolerable for the middle, and in turn rendering the Metaverse useless. But to do that in a less social network oriented way, one must first deconstruct aesthetics of each of these classes. Within the three middle classes, the blue collar class desires "winning" in an event, the white-collar middle desires significance in any community, and the professional class desires yuppie comforts. In all instances, personal identity is prioritized over the pure physical (grass-touching) or the pure spiritual (meditate and read). Atomization of an unsafe meatspace makes internet socialization comparably tolerable. https://danco.substack.com/p/michael-dwight-and-andy-the-three https://hackernoon.com/on-the-infestation-of-small-souled-bugmen-6561ae922e07

What are the steps to initiate small pocket dimensions of meatspace that is fun and joyous? A hint can be found in internet subgenres of art. For example, the whole "backrooms" and "liminal" photography genre hints at the need for communal third spaces as abandoned malls and hotels. Urbex sounds like an adventure but it can be considered trespassing. Also a similar sentiment about "traumacore" hints that going to a friend's house is a thing of the past, as the disenfranchised are the most likely to not have access to private spaces.