Poetic Prose on Evil, Written on the Occasion of Having Purchased a Venus Flytrap

Carnivorous plants and their horrendous little red mouths 🐜

What does evil look like? Darkness. Tones of black and purple and gray, dulled, lifeless — evil looks like death. It looks like the absence of anything good. It looks like emptiness. It looks like The Void. Quite often evil also has the brown or bluish guise of foulness: buzzing insects and spreading fungus. But equally often it looks like danger. If a bright color is involved it shall be red: the red of blood, the red of violence. The red of ripped threads of flesh, dangling, in the aftermath of a meal, from the maw of an apex predator.

Contrast with plants. Plants are non-evil. They feed us, and give us shade, and beauty; we make gardens out of them. When flora is meant to evoke malevolence it is made dead. Picture a grove of dead trees with gnarled, gray branches over a stormy black sky background. Living plants are, instead, a sunny, bright green: a decidedly good color. In past times, when nature was less beloved, when wilderness loomed as a threat, green may have been more ambiguous; it brought to mind the sickness of liver failure, or the poison of chlorine gas. But today we love green and we love plants. Plants take nothing by force; they weave their sustenance from sunbeams. They are the silent prophets of a solarpunk utopia.1

Most of them are, at any rate.

Why aren’t you just green, my little venus flytrap? Why did nature give you, uniquely among all plants, many sets of jaws, complete with little teeth? And why did it elect to paint them the color of animal flesh?

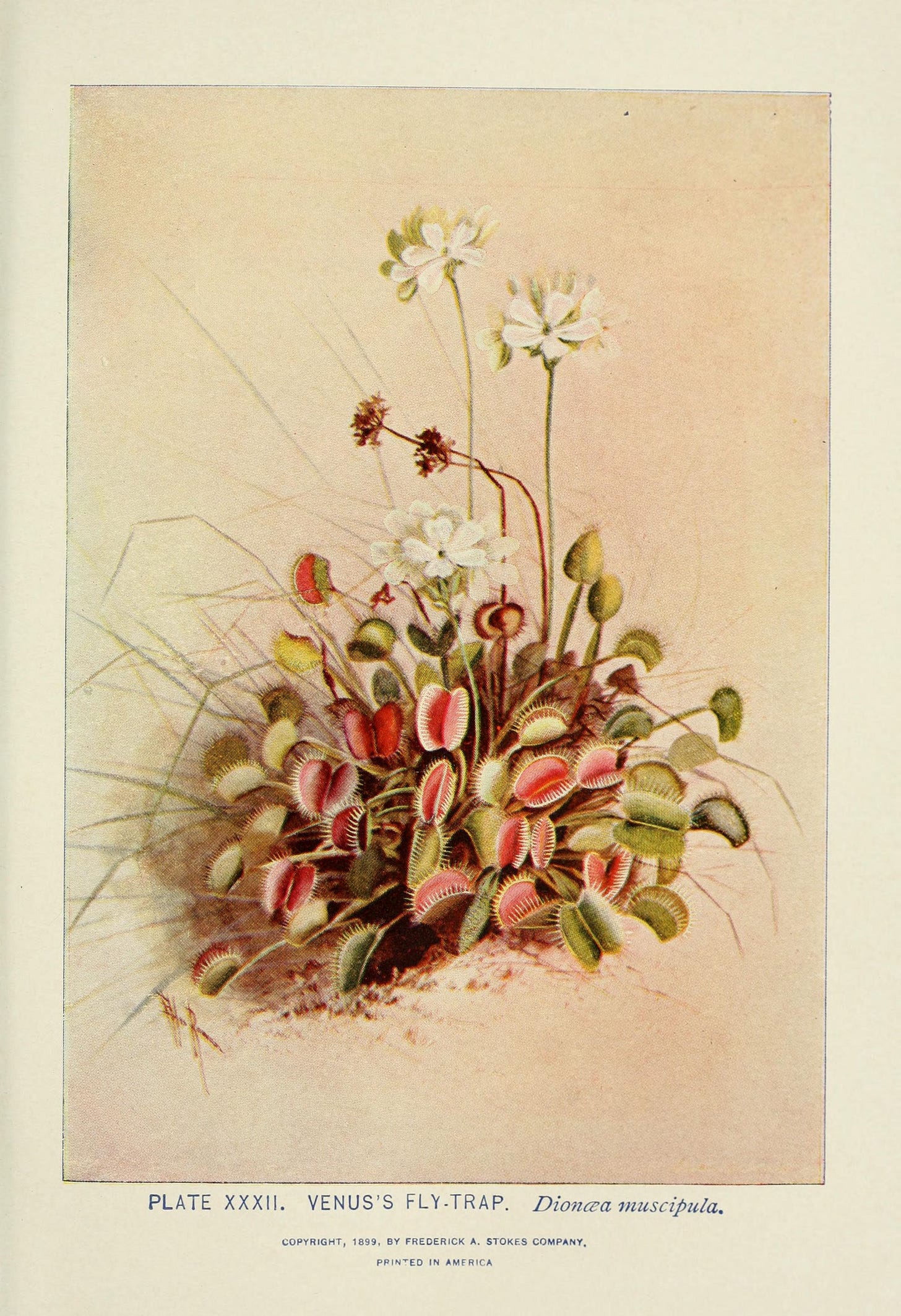

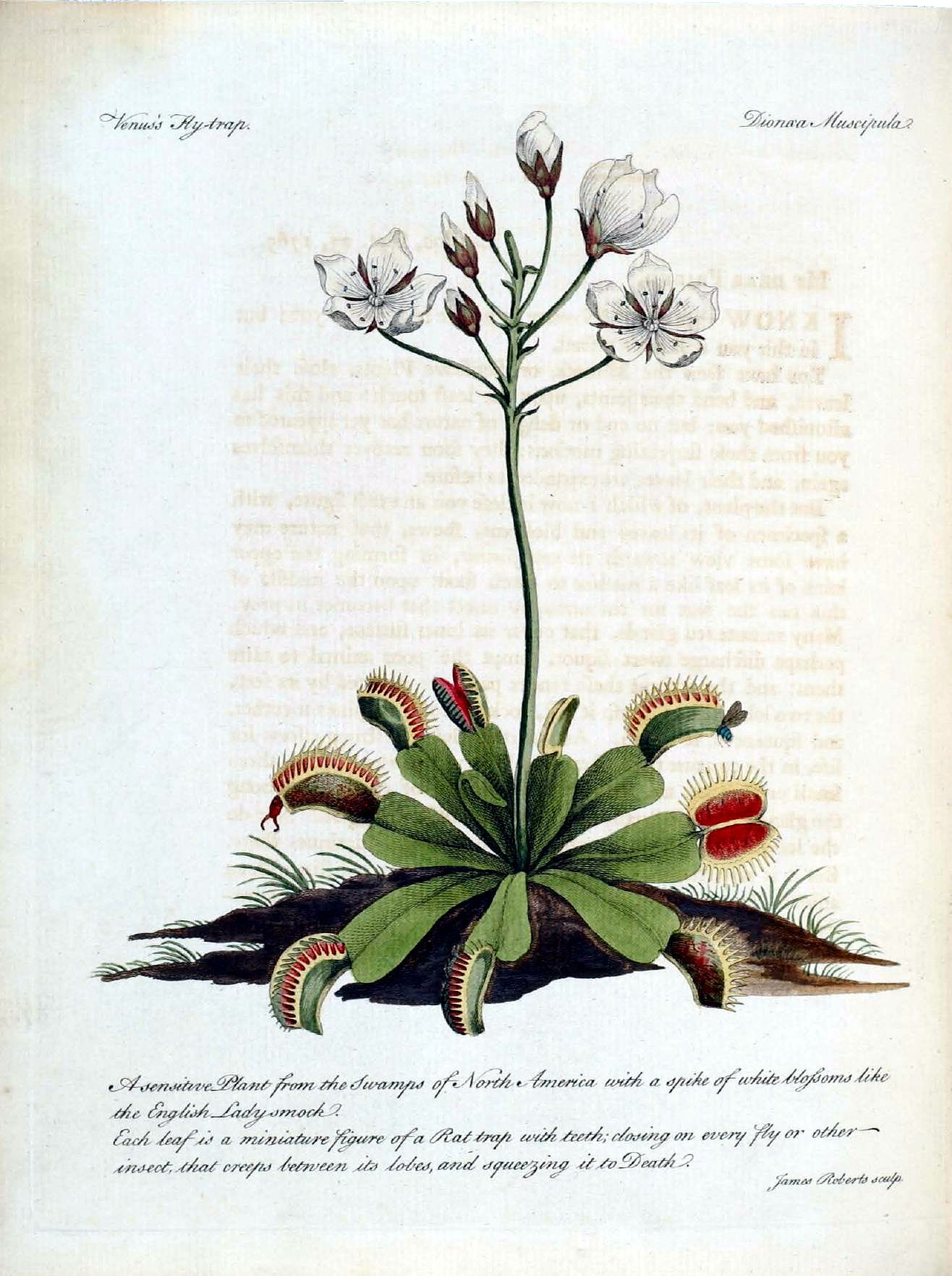

I bought you a few days ago, at the local market, fulfilling a childhood dream. On several occasions in my life I have visited bogs, those wetlands with poor, water-drenched soil where plants evolve insectivory to glean the nutrients they cannot otherwise find. I have been fascinated by the purplish pitchers of Sarracenia, and the sticky, dewy red hairs of Drosera. (Why are you red, all of you?) But the venus flytrap is in its own category. It grows only in a tiny region of the world, shared between the Carolinas of the American Eastern Seaboard. It descends from Drosera, the botanists believe; the sticky, dewy red hairs became the thin teeth and the six sensitive trigger hairs inside the jaws. The venus flytrap is the only one, together with an aquatic cousin, that quickly, spectacularly closes its horrendous lips upon its unsuspecting prey.

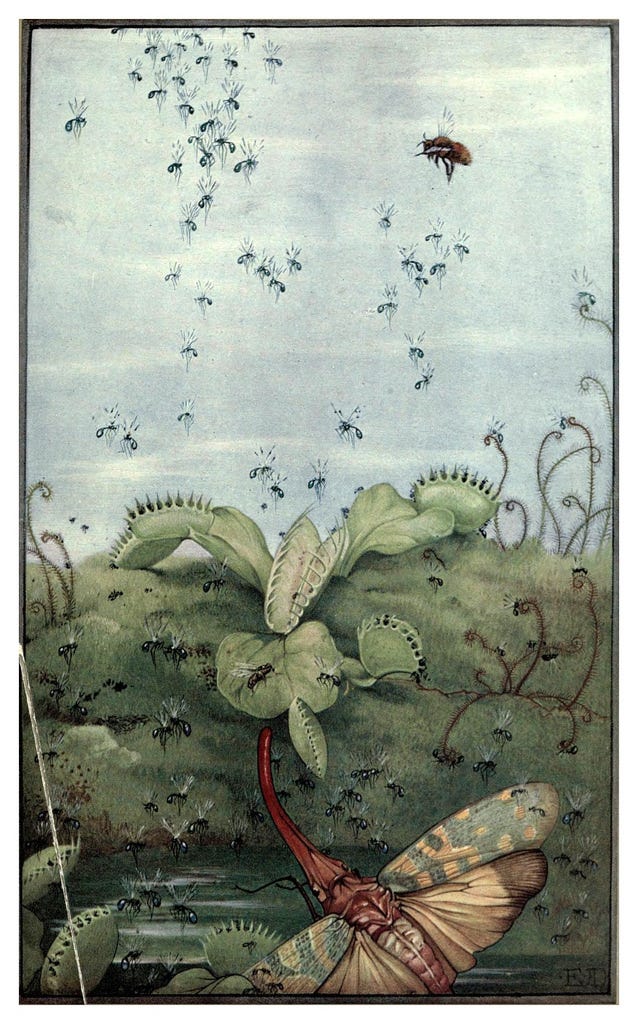

You look so evil, venus flytrap. You seem a traitor to your kind. Plants aren’t supposed to prey on animals. They aren’t supposed to display rapid movement. And they certainly aren’t supposed to look like they have a dozen small mouths, ready to swallow and digest anything that walks into the trap.

To see what you were capable of, I fed you an ant. Two, in fact — but the first lucky one escaped. You closed your jaws, and for half a minute or so the ant panicked, frantically walking around the small space it was stuck in. It finally found a sufficiently large gap between your teeth and crawled its way out. Had it failed, you would have gradually strengthened your grip until the trap was shut tight, and then you would have begun secreting digestive enzymes. Within but a week, there would have been no more ant. The trap would have reopened, hungry for more.

This atrocious scenario is what is currently happening to the second ant. To make sure that it wouldn’t escape, and that you wouldn’t waste your energy, I weakened it first. I see it now, forming a little bump within your tight leaf trap. You are digesting it. Soon its minerals and proteins will be part of you.

I feel weirdly bad about this. I cannot say I care much about the welfare of ants. But being trapped alive in a digestive pouch while enzymes dissolve you strikes me as a particularly dreadful way to die.

And it is, I suspect, made worse by the apparent unnaturalness of all this. Feeding a mouse to a python would be uncomfortable but not revolting: it is the normal way of the world. Feeding an animal, even a minute one, to a plant, is closer to primal horror. We imagine ourselves in the ant’s place. We shudder at being defeated by a living thing that doesn’t even have a nervous system, that doesn’t even notice it is digesting you. We are glad to be reminded that no plant large enough to kill a human being exists; but we cannot resist putting such things into our stories, contributing to a long tradition of man-eating plant legends and pulp fiction tales.

But of course it is natural. Plant carnivory has evolved at least twelve times, forming a diverse group of more than 500 species (most of which, apparently, are at least partly red), not to mention the 300 or so that exhibit protocarnivorous traits. Nature is thrifty; when it makes sense for a plant to collect the essence of insects, spiders, or small frogs and lizards, it shall do so. Nothing goes to waste in the harsh jungle of survival. If evil is called for, then evil shall arise. Nature certainly does not care one way or another.

Do you know, venus flytrap, that you are evil? Of course you do not in the sense that we humans conceive knowledge; but do your genes know? Did your DNA arrange itself, through an effort by natural selection, specifically so that it would give rise to those horrendous predatory mouths?

I think you do know. Because like all flowering plants, you also know beauty. Though the crawling insect is your prey, the flying bug is your ally: you need to be pollinated, and for this you produce beautiful, five-petalled flowers, which of course you put at the end of a long stem, away from the bright red traps. Your flowers are white, the least evil color of all. They look so incredibly normal. The stereotypical essence of what a flower should be. Nothing, absolutely nothing to be suspicious of, for the bees and beetles who visit you at a safe distance from the ground.

Humans gave you a name to match your dual nature. Venus, for the goddess of love; Dionaea in Latin means the same thing (“daughter of Dione,” i.e. Aphrodite). Flytrap, or its literal equivalent muscipula, is self-evident.2 You are beautiful and yet you are a trap. I suppose many things are like you in that respect.

It is unlikely, I think, that I will see you flower. Venus flytraps are known to be difficult to care for. I water you abundantly with distilled water (you wouldn’t want your minerals from your water, no! you insist on getting them from digested prey!), but surely someday I will do something wrong. Not feed you enough ants, perhaps, or not provide you with enough sunlight (you are partly solarpunk, after all). Then you will wither and die. I wonder if I shall be, secretly, relieved when that happens.

Confession: I never do this, but I asked an AI to help make this paragraph more poetic. I rejected most of it, except a few good synonyms here and there, but I did keep this last sentence because it goes hard.

Though ants, spiders, and beetles are the flytrap’s prey of choice, rather than flies or other flying insects.

"Prophets of a solarpunk utopia" is how I'm now going to think about all plants with weird leaves or flowers. Thanks for tickling the machine and selecting this gem.

I loved reading this! Also totally intrigued by what solarpunk is? I’m super interested in questions about monstrosity, good and evil, and if any of those things really exist, or exist in isolation from the other two. I sort of now want a Venus flytrap, but am also slightly scared that having one might turn me into a villainous mastermind.