An Adventure in Smoke Detection

Join me in trying to vet one particular extremely niche fact! 🚬

A few weeks ago, I was told that I was required to change my 10-year-old smoke detector. This made me realize that I hadn’t added the smoke detector to my tech tree database,1 and in fact that I knew nothing about when smoke detectors were invented or how they work. So I did what I do in such circumstances, which is to start by checking the relevant Wikipedia page’s “History” section.

According to Wikipedia, the smoke detector has antecedents in heat-based fire alarms starting around 1890, but those wouldn’t be detecting smoke. The earliest such device seems to appear in the 1930s:

In the late 1930s, Swiss physicist Walter Jaeger attempted to invent a sensor for poison gas.[6] He expected the gas entering the sensor to bind to ionized air molecules and thereby alter an electric current in a circuit of the instrument.[6] However, his device did not achieve its purpose as small concentrations of gas did not affect the sensor's conductivity.[6] Frustrated, Jaeger lit a cigarette and was surprised to notice that a meter on the instrument had registered a drop in current.[7] Unlike poison gas, the smoke particles from his cigarette were able to alter the circuit's current.[7] Jaeger's experiment was one of the developments that paved the way for the modern smoke detector.[7]

This is a really cute story! In the tech tree, it suggests a connection from both poison gas and the cigarette. I like connections like this, because they show how technology from a given field (like chemical weapons or recreational smoking) can influence another, totally different field (like fire safety). It’s also always fun to read about serendipitous discoveries and witness the randomness that is inherent in innovation.

But I try to be careful about truth, and especially about stories that are possibly a little too cute. In the Roots of Progress Blog-Building Intensive that I’m currently a part of, we discussed epistemic standards a few weeks ago. Progress studies, as a subculture, wants to be rigorous and truth-seeking, since studying progress often means studying the history of inventions, policies, and other niche things that tend to be rife with apocryphal information. Examples include “the Vikings wore horned helmets” (they did not, it’s a 19th century invention) and “the invention of petroleum-based fuels saved the whales from extinction by replacing whale oil in lighting” (in fact petroleum fuels allowed ships to hunt for whales more efficiently, and the decrease in whale populations continued for another century).

I deal with this all the time as I compile data for the tech tree. Though I base a lot of it on Wikipedia,2 I try to always make an effort to be reasonably confident that the data is true. It’s often sufficient to cross-reference a couple of related Wikipedia pages and check whether citations exist and are credible. But in this case, that didn’t work, and doubts started to creep in.

It begins when I try to learn more about Walter Jaeger. For any technology in the tech tree, I usually read the inventor’s Wikipedia page as a sanity check, and also because it often helps record the time and place of the invention. But it turns out that Mr. Jaeger doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. This is a little suspicious, but not that problematic; Wikipedia isn’t expected to contain everything.

So I google him. The first Google result is the smoke detector Wikipedia page that I was just on. A bad sign. The second is an obituary for a Walter Jaeger who was born in 1935 in Poland, so very unlikely to invent smoke detectors in late 1930s Switzerland. Then we get image portraits of various Walter Jaegers, which is when I realize that this is a very common German name and that it may be hard to disentangle a Walter Jaeger (or Jäger) from another.

I check the German Wikipedia for Walter Jäger; nine of them are mentioned, but only two have an actual page, and most don’t fit the details (physicist, Swiss, active in the 1930s). One Walter Jaeger is Swiss and received a doctorate in chemistry in 1937, which is close, but the translated page doesn’t mention smoke detectors, and he is much more well-known for being a politician. I search Google some more. There’s a Walter Jager who’s a consultant in environmental compliance in Ottawa, according to LinkedIn. Another Walter Jäger was an Oberleutnant on a U-boot in the Nazi Kriegsmarine. The Discogs database mentions a Walter Jaeger who’s a German multi-instrumentalist and instrument maker, born in 1958. Okay, this isn’t going anywhere.

I go back to the smoke detector page. Wikipedia lists two references, still visible in the quote above as [6] and [7]. Reference [6] is a “Fact Sheet on Smoke Detectors” on the website of the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Presumably the NRC is talking about smoke detectors because they use radioactive materials. (How do smoke detectors work, anyway? Click the footnote to learn more!3) This page, which was written in 2013, does tell the Walter Jaeger story—

In the late 1930s, a Swiss physicist was working on a sensor for detecting poison gas. Walter Jaeger's device failed to register small amounts of gas. Frustrated, he lit a cigarette—and the smoke moved the meter on his gadget. Jaeger's experiment helped pave the way for today's smoke detector.

—but doesn’t cite any further sources. I suppose it’s maybe a little authoritative because it’s a government agency, but not by much. I email them to ask about it, but do not expect a response.

Reference [7], meanwhile, is a book titled The World's Best Business Ideas, also from 2013. It’s almost certainly not a primary source, doesn’t seem particularly trustable, and would cost me $25 on Amazon, which is more than I’m willing to spend to ascertain one very niche fact.

Okay. I google around. The story is oft-repeated on various websites (80% of which are blogs from providers of fire safety services), but the details are basically always the same, with minor rephrasing. Examples here, here, here, here, and here, among many others.

I ask Claude to search for me, mentioning that I’m a little skeptical of the story. Claude isn’t any better than I am at web searches, but it might stumble upon something I’ve missed. It finds a few things, but agrees with me (though perhaps because I primed it this way…) that this looks like mostly circular referencing. Claude concludes:

My assessment: The Walter Jaeger cigarette story has the hallmarks of an appealing but potentially apocryphal tale that may have been embellished over time. While it's possible Jaeger made contributions to ionization detection principles, the specific anecdote about the cigarette smoke accident appears to lack solid primary documentation. The story serves as good marketing for the technology but should be viewed with skepticism from a historical accuracy standpoint.

I also notice that every mention of the story dates from the 2010s or later. For something supposed to have happened in the 1930s, that’s suspicious. I search Google and Google Scholar using date filters, and find a few mentions in the 1990s, but nothing earlier.

The only thing that’s left is to brush up my German Google Translate skills and search outside the Anglophone web. In German, a smoke detector is apparently a Rauchmelder. I google “Rauchmelder Walter Jäger.” Most of what I find is the same kind of sourceless rehash as in English, though maybe with a little more depth:

Ende der 30er Jahre kam dem Physiker Walter Jäger der Zufall zur Hilfe. Bei dem Versuch mit einer Ionisationskammer Giftgas zu erkennen, stellte er fest das Zigarettenrauch deutlich besser erkannt wurde. Daraufhin gründeten Walter Jäger, Ernst Meili und Hans Lutz von Gugelberg die Firma Cerberus.

At the end of the 1930s, chance came to the aid of physicist Walter Jäger. While experimenting with an ionization chamber to detect poisonous gas, he discovered that cigarette smoke was significantly more effective. Walter Jäger, Ernst Meili, and Hans Lutz von Gugelberg subsequently founded the Cerberus company. (source)

But more importantly, a few results down the list, aha! I find a link to a patent on Google Patents. And this patent cites three patents from the 1930s by Walter Jaeger!! One of which is for a Rauchmelder!!!

This is my first clear evidence that Walter Jaeger is real. But none of the patents, translated by Claude, say anything about a serendipitous discovery involving cigarettes and poison gas. They are, as expected of patents, dry technical stuff.

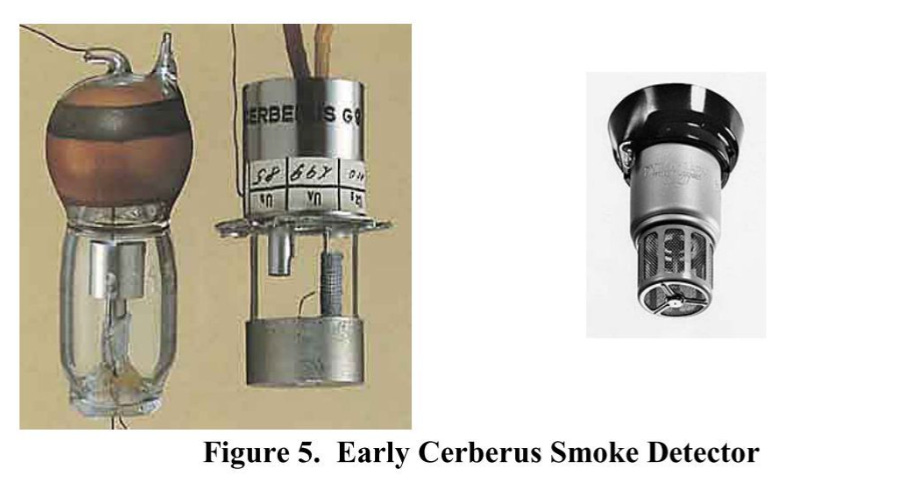

This clue doesn’t really solve anything, but it encourages me to keep looking. I turn my attention to another Swiss physicist whose name I’ve seen a few times at this point: Ernst Meili.4 The original smoke detector Wikipedia article mentioned him just after Jaeger: “In 1939, Swiss physicist Ernst Meili devised an ionization chamber device capable of detecting combustible gases in mines.” Maybe he’s the actual inventor I should put in the tree if Jaeger can’t be ascertained. There isn’t a page about Meili on en.wikipedia.org, but there is one on de.wikipedia.org. Interestingly, it says that Meili joined, in 1941, a company named Cerberus GmbH, founded by Walter Jäger. This also fits some of the random German Google hits (see above). Also, Cerberus is still today a legacy brand of fire safety products, now part of Siemens. We may be inching closer to something concrete here.

The Ernst Meili Wikipedia page cites some sources that seem more trustworthy than what I’ve seen before. One in particular is a 2006 publication by Hans Tobler, a researcher at Cerberus, in the trade journal of Electrosuisse, the Swiss association of electrical companies. It is on the 50-year history of Cerberus in the field of ionization smoke detectors:

Die Ära der Brandmelder begann mit einer Publikation im SEV-Bulletin anno 1940 von Walter Jäger, Physiker und früherer Mitstudent von Ernst Meili: «Die Ionisationskammer als Feuermelder». Ein Jahr darauf gründeten Meili und Jäger die Cerberus GmbH in Bad Ragaz, mit der Absicht, Brand- und Intrusionsmelder zu entwickeln und zu fabrizieren: Es begann eine dramatische Geschichte einer Firma, die 1998 juristisch und 2005 physisch in Männedorf ein Ende fand.

The era of fire detectors began with a publication in the SEV Bulletin in 1940 by Walter Jäger, a physicist and former student of Ernst Meili: "The Ionization Chamber as a Fire Detector." One year later, Meili and Jäger founded Cerberus GmbH in Bad Ragaz with the intention of developing and manufacturing fire and intrusion detectors. Thus began a dramatic story of a company that ended legally in 1998 and physically in Männedorf in 2005.

Okay, so Jäger was a student of, and then cofounder with, Ernst Meili. [Addendum: not at all! I think this is a translation error by whichever LLM I used for this — mitstudent means “fellow student,” not “student of”.] The story of this Cerberus company varies a bit (was it cofounded by Jäger and Meili, or only by Jäger and Meili joined later? were other Swiss physicists involved?) but at least it seems pretty certain at this point that it was the first company created to manufacture ionization smoke detectors, in the 1940s, and that these two Swiss gentlemen had something to do with it. Still, though, no mention of the cigarette story.

The name Cerberus is a pretty good thing to search for, except of course that it mostly leads to paintings and pottery art of multi-headed dogs who guard the underworld.

But combined in a Google query like “Cerberus GmbH smoke detector history,” I actually get somewhere. A report titled “History of Smoke Detection,” prepared by James A. Milke for Siemens in 2010 and found on a weird website that showers me with ads every time I try to turn a page, contains a few good nuggets. First, it seems that the first actual smoke detection occurred earlier, the work of yet another Swiss physicist, Heinrich Greinacher, in 1922, who was trying to measure dust content in air. Second, it confirms that Jäger was trying to build a poison gas detector, and that he noticed it could be used for smoke after he lit a cigarette! Third, it mentions some other actual predecessor techs to the smoke detector: a triode with cold cathode to amplify the ionization signal, and radium as the radioactive source to cause the ionization. Fourth, and most importantly: the report abundantly cites “Meili 1990.”

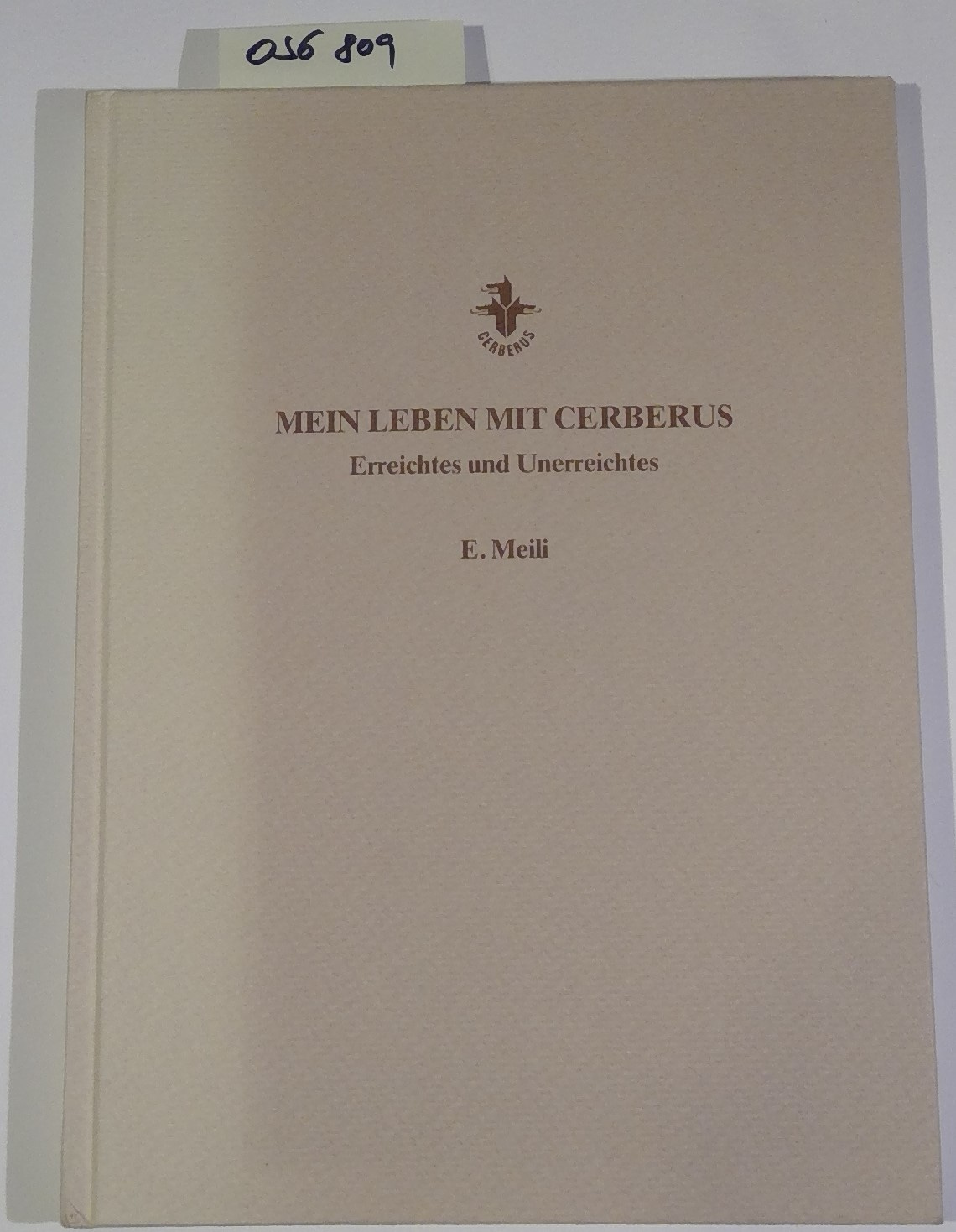

“Meili 1990” turns out to be a book by Ernst Meili published in 1985 titled Mein Leben mit Cerberus. Erreichtes und Unerreichtes. An English version, My Life With Cerberus: Successes and Setbacks, was apparently published in 1990. It seems pretty obscure. The German version exists on Google Books, but with very little info. The closest library that has it according to WorldCat is 5,988 kilometers from my location, i.e. in Zurich. The English version isn’t even on WorldCat and returns only three Google results.

This is where I decide to stop. It seems quite plausible that the cigarette story is told in this autobiography by Meili: that’s exactly the sort of anecdote that would be fun for Meili to tell. It also fits the fact that I couldn’t find references to the story before the 1990s. But going further would be too much effort. The lecture about epistemics at the BBI did emphasize that spending 20 hours on figuring out one tiny fact may not always quite be the best possible usage of your time.

Also, that title sounds like a young adult novel aimed at adolescent fans of Greek myth. It makes me want to play the video game Hades. Has Hades II come out yet?

No, sorry, I am not done.

Several days later, I am told what I already know, which is that my blog post draft is lacking a payoff. It deflates towards the end. If I’m serious about this essay, I should find a way to get access to Mein Leben mit Cerberus. I should, at the very least, send out some more emails.

By coincidence, on the same day, the US NRC replies to my inquiry and suggests that I contact Dr. James A. Milke, who wrote the report cited above. Dr. Milke is a professor emeritus in fire protection engineering at the University of Maryland. I shoot an email, and the reply comes almost immediately:

That history is correct. I wrote a short report for Siemens several years ago about the history of smoke detection. They loaned the Meili book to me as one resource used to write that report. Unfortunately, I had to return the book.

Seems like the confirmation I was looking for! But I would still like to see the contents of the book. By googling more for it, I find a publication called Sensors in Intelligent Buildings, in which an article by Marc Thuillard cites the Meili book. It turns out that Thuillard was a Cerberus employee! I find his email on an article about archeoastronomy — puzzling, but his ResearchGate page does contain smoke detector stuff once you scroll past all the articles with titles like “Computational Approaches to Myths Analysis: Application to the Cosmic Hunt.” I shoot an email, and the reply comes almost immediately, in French: He has heard the anecdote, but has forgotten the details. He adds that he left Cerberus twenty-five years ago, and now devotes his time to a YouTube channel about ethno-astronomy. Merci, monsieur Thuillard.

I also contact Siemens directly, but the reply will probably not come almost immediately. I still don’t have the book. Should I actually purchase it? Or maybe I know someone in Switzerland who is willing to walk into the library and look it up for me? No, almost certainly not. Still, let’s try it. I tweet the following:

… and find this person in, like, 10 minutes????? A Twitter mutual-of-a-mutual, Benjamin Schneider, tells me I’m in luck: he lives right next to the Zentralbibliothek in Zurich, he happens to have a lot of free time (I gather from his website that he’s looking for work, maybe hire him??), and most importantly, he “can’t resist a good nerdsnipe.” This long shot has somehow resulted into a perfect hole-in-one, wtf. The next day, Benjamin goes to the library, scans the entire book with his phone, and sends me the relevant passages with a GPT-5 translation:

Nach Aussagen von W. Jaeger hatte er ursprünglich – noch vor Kriegsausbruch – die Idee, mit Hilfe einer Ionisationskammer einen Giftgasanzeiger zu entwickeln. Da die fraglichen Gaskonzentrationen im militärischen Einsatz ausserordentlich klein sind, habe sich das Vorhaben als aussichtslos erwiesen. Er habe dabei als Zigarettenraucher zufällig die starken Stromschwankungen beim Eindringen von Rauch in eine Ionisationskammer festgestellt.

According to W. Jaeger, he originally—before the outbreak of war—had the idea of developing a poison gas detector using an ionization chamber. Since the gas concentrations in military use were extremely small, the project proved to be hopeless. However, as a cigarette smoker, he accidentally noticed the strong current fluctuations when smoke entered an ionization chamber.

Well, there we go. My quest is done. The story is true.

Or, almost? There isn’t much of a narrative here. Nothing about W. Jaeger becoming “frustrated” and lighting a cigarette because his device doesn’t work. That’s a small thing, but by now I’m almost certain that’s an embellishment that appeared when the story began circulating as a meme on the internet.

Paging through the LLM-translated book, I learn a few more things: for example, that Jaeger was Meili’s “bester Studienfreund,” i.e. best friend during their studies, I think at ETH Zurich in physics. Jaeger graduated one semester after Meili. So the idea that he was a student of Meili, which we saw in that 2006 publication, seems plain wrong. [Addendum: it’s indeed wrong but because of a translation error! Be careful about LLM translation, folks!] We also learn that Jaeger came from a wealthy family, which allowed him to pursue his passion for invention after graduation without worrying about earning a living. It seems that Jaeger did not get a PhD, let alone in chemistry, so he’s definitely not the politician gentleman whose picture we saw earlier.

Meili gives more detail about the company’s founding. Jaeger and him hadn’t been in touch much after graduation, but Jaeger contacted him on June 3, 1940, to suggest building a smoke detector company together. This contradicts the following passage from Wikipedia:

In 1939, Swiss physicist Ernst Meili devised an ionization chamber device capable of detecting combustible gases in mines.[8] He also invented a cold cathode tube that could amplify the small signal generated by the detection mechanism so that it was strong enough to activate an alarm.[8]

There is no indication in his autobiography that Meili worked on smoke detectors at all until 1940; he had instead been involved in radio tech at the companies Telefunken and Hofrela, but didn’t like working as an employee and was pessimistically considering going back to ETH for grad school when Jaeger suggested doing a startup together. (This sort of story definitely still feels familiar in 2025...) The company had two other cofounders, Rudolf Jaeger (Walter’s brother) and a friend of Walter’s wife named Grita Büchel. There’s no mention of a “Hans Lutz von Gugelberg” which I saw named as a cofounder on at least one website.

There’s also some interesting background on Jaeger’s invention, confirming Greinacher’s 1922 publication and also attributing some contributions by Malsallez and Breitmann in France in 1937-38. Meili muses that it may have been an independent development from theirs, and the invention was “in the air,” picked up simultaneously in different places, as often happens in the history of technology.

But enough about the contents of the book.5 I found the info I was looking for. What did I learn in the process?

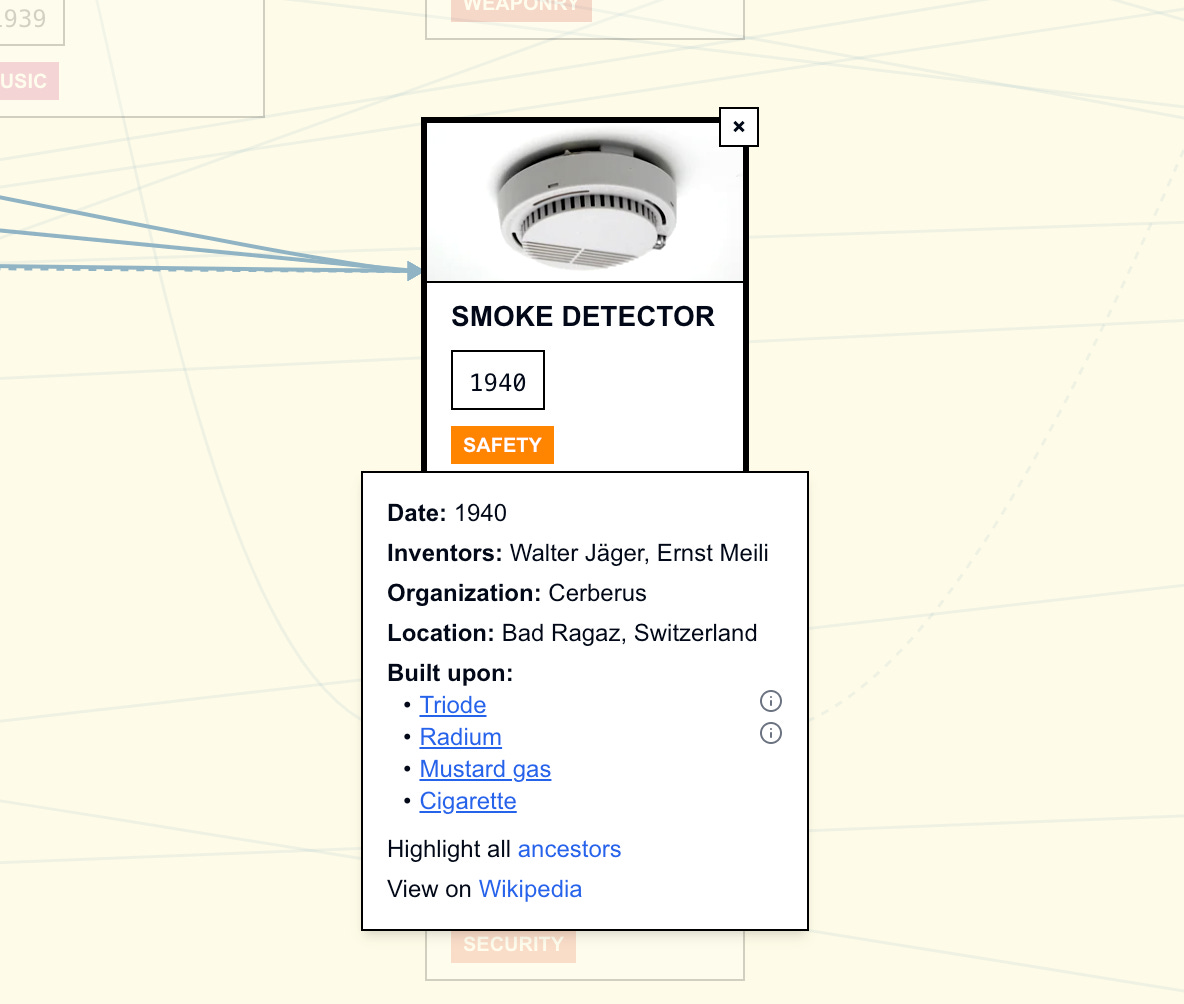

First, quite a bit of lore about the humble smoke detector. For my tech tree, I’ll attribute it to both Jaeger and Meili, in Bad Ragaz, Switzerland, and date it to 1940 — which seems to be when the cigarette anecdote occurred, and when they made the first mass-produced model, F1. The smoke detector’s predecessor techs will include radium, triodes, the cigarette, and mustard gas (I’m making a reasonable guess that this would be one of the poison gases Jaeger had been trying to detect).

Second, that my internal smoke fake story detector doesn’t work that well. There was a moment early on in this quest when I was convinced I had found an apocryphal fact and would heroically slay it. But Wikipedia was mostly correct after all. On balance, I’m glad of this outcome; the story being false would have been sad; the world is a little bit cooler for this story being true and documented.

Third, however, I did discover that quite a few of the story details, whether on Wikipedia, random company blogs, and even in specialized publications, are wrong or embellished. It obviously doesn’t matter that much to suggest that Jaeger was frustrated by his poison gas detector (it’s pretty plausible, after all), or to name the wrong set of cofounders. But in a world where any transmission of information has an error rate, and where the errors can therefore accumulate as the info circulates, there is value in digging deep for the primary source of a suspicious fact, even if you don’t end up debunking it. It’s a kind of epistemic hygiene, and everybody benefits when everybody does their part cleaning up the commons.6

Fourth, I think I learned quite a bit about myself! I’ve dug deep for primary sources of niche facts many times, but never really took the time to document the process. I now have a more detailed mental model of what it actually means to do research online. I also have seen the benefits of directly emailing people, which I don’t naturally think of doing for some reason.

Oh, and this article motivated me to finally replace my smoke detector. Now I will not die in a fire, which is pretty cool. I even have a carbon monoxide detector now. Maybe I’ll add that to the tech tree next.

This was my second post as part of the Roots of Progress Institute’s Blog-Building Intensive. Special thanks to Mike Riggs for encouraging me to dig deeper, to Benjamin Schneider for going to the Zurich library to scan that book for me, to Ulkar Aghayeva for connecting me to Benjamin, and to blog fellow Alexander Kustov for feedback.

As a method of getting ideas for what to add to the tech tree, this is a bit on the random side, but not that much. Ideas really do come from anywhere.

For the tech tree, I use Wikipedia a lot, even though it’s not necessarily the most reliable source, for several reasons:

There usually is a History section, which is not always easy to find on other websites discussing a technology.

Niche historical questions are rarely controversial (though sometimes they are!), so political biases aren’t a huge concern.

Wikipedia citations are pretty good, it’s often easy to verify just enough to reach a basic level of trust.

It depends on the topic, but I don’t think Wikipedia is actually less reliable than any equivalent resource. A single academic paper or history book may be more reliable, but the set of all academic papers or books contains a lot of mistakes, too, and figuring out which publications to trust is no trivial task.

Smoke detectors use either optics or radiation. In the latter, a radioactive substance, usually a tiny amount of americium-241 (or radium in old models, since americium was discovered in 1944) emits alpha particles, which are made of two protons and two neutrons. The alpha particles interact with air particles and ionize them, i.e. make electrically neutral particles become positive or negative. This allows an electric current to pass. When smoke enters the device, the current passes less well, which triggers the detector.

Photoelectric (or optical) smoke detectors were invented later, apparently in the 1970s, and rely on detecting a change in the intensity of a small light source due to the presence of smoke.

If you’re somehow interested in the full history of Cerberus, let me know — I have the PDF!

Speaking of, I suppose I should correct Wikipedia now. (Said nobody who ever found something wrong on Wikipedia ever.)

Wow! Superb writing, it feels like a crime thriller, with suspense, dead ends, and twists. The inventor of the smoke detector was this guy the whole time!!!

Just so you know, you can still die in fire even if you have a fire detector in your house. 😉

This was so much fun, thanks for bringing readers along with you.